First published on 02/20/2021, and last updated on 06/18/2025

‘Our ancestors made sustainable use of resources from the top of the mountains down to our oceans and even past our horizon’

By Kinohi Pizarro, Lohe Pono Fellow at KUA – Kuaʻāina Ulu ʻAuamo (ICCA Consortium Member)

Adapted from a presentation in a recent peer learning and exchange event in the ICCA Consortium’s community fisheries initiative

My name is Kinohi Pizarro and I was born and raised in Waimanalo on the island of Oʻahu. I consider myself a lifelong learner, a mother, a kiaʻi loko, a mentor, and a friend. Each of these abilities requires one to be a great listener. So, when the opportunity at KUA came up to be a part of a fellowship called Lohe Pono, I went for it.

Lohe Pono is the act of radical learning through listening, respectful listening, listening well, listening intently to; the list goes on and on. So many ways to define this term. I believe we listen with our naʻau (intuition) in regard to some of the most key, vital, and necessary components for our existence and our survival as people. Our decision-making tool lies in our naʻau. We need to relearn how to trust it.

Here I will be sharing with you about fishponds and how they are related to our food systems and nearshore fisheries. I am a mother of four children, and we have been around fishponds since birth. But this fishpond- Heeia fishpond (pictured below) is special. We have been learning from this fishpond for the past twelve years of our lives.

Heeia fishpond. This photo of us is exactly what it looks like, a happy family-selfie. Photo © Kinohi Pizarro

Before I go into the stories of fishponds and communities in Hawaii, let us take a brief world-tour, see some fishing grounds, ponds, and most importantly fish traps.

We know of a now-famous fish trap found in Wales, said to be dated back more than a thousand years. Fish would swim inshore on the higher tides and when the tide would recede, they would try to swim out and they would be corralled to an area where someone would be waiting with a net to capture them. Another ancient fish trap can be found in Penghu, Taiwan. Penghu has over 570 fish weirs. These also work with the tide and were said to have been built over 700 years ago. The last one is from Huahine, Tahiti. For ages, our peoples in the Pacific have been using traps to catch fish. In the Pacific native, people created these food systems with their innovative skills and ingenuity. In addition to going fishing beyond shorelines, our people used fish traps made of local common resources such as rocks. Genius!

(Top) This ancient fishpond in Pembrokeshire, Wales was spotted in 2009 by Google Earth’s aerial photographs. (Bottom left) Twin-Heart Fish Trap in Cimei, Penghu, Taiwan. Photo © Sutej Hugu. (Bottom right) Fish trap in Huahine, Tahiti. Photo © Pierre Lesage

These are all in our ancestral memories as native, ocean, people! Fishponds and fish-traps have been an important part of Indigenous and traditional food systems.

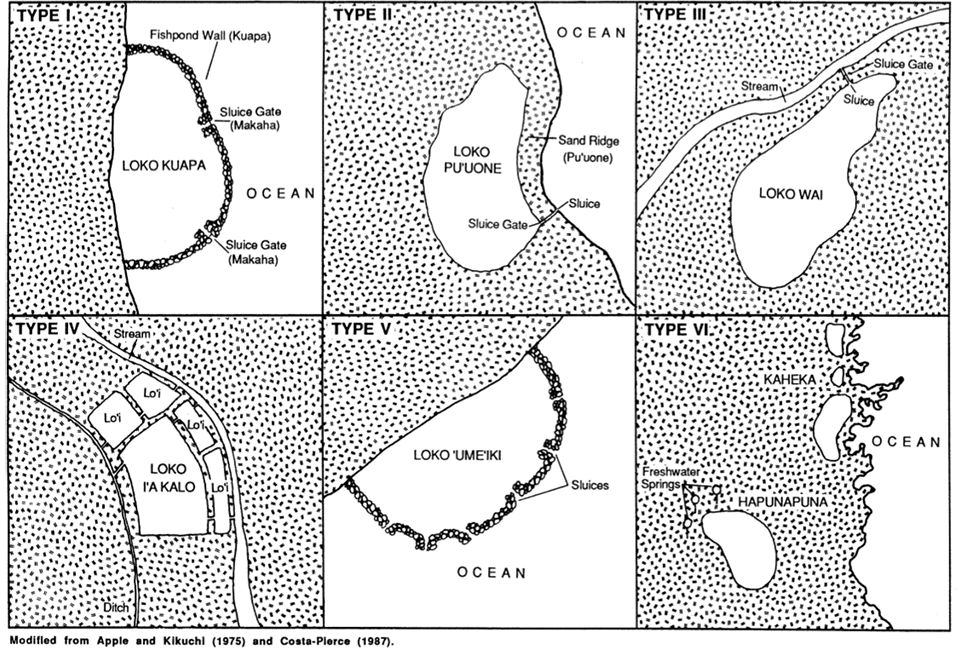

Coming back to Hawaii, while our main source of starch- our main staple taro or kalo was always grown in floodplains, our main source of protein was fish. There are over four hundred recorded fishponds from our oral histories passed down. Many remnants of these fishponds still exist and are being restored today. There are six different types of fishponds with fresh, brackish, and saltwater to attract, hold and capture fish. These systems have proven to be an efficient, effective, sustainable component of our food system.

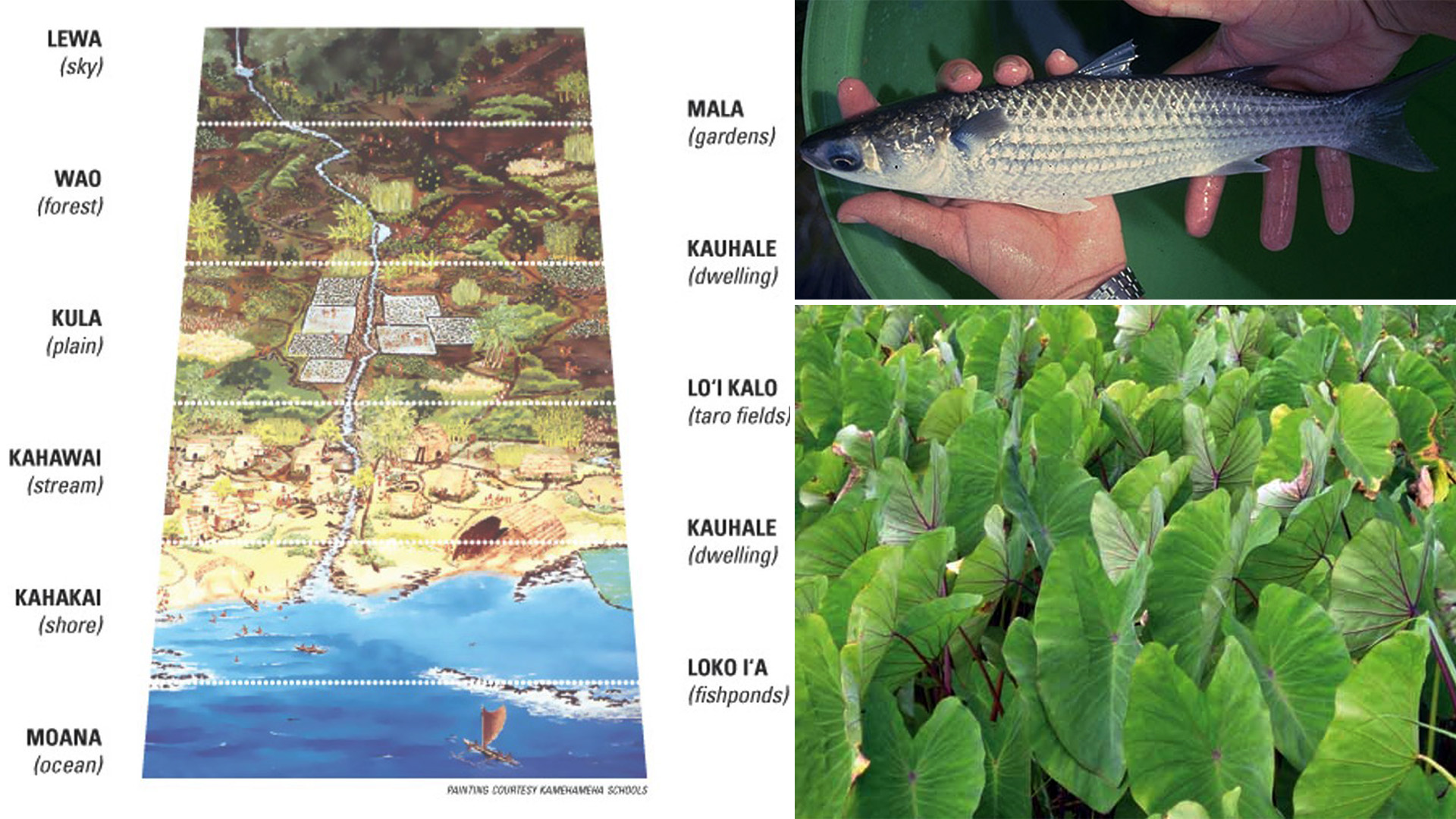

Ahupuaʻa land use system. (Right) Painting courtesy by Kamehameha Schools, (Right top and bottom). Photo © Kelii Kotubetey

Our ancestors made sustainable use of resources from the top of the mountains down to our oceans and even past our horizon. Our traditional land use systems, such as Ahupuaʻa were very sustainable for each area of land to sustain its people with the resources that were available to them. In this land-use system, Loko i’a, or the fishponds are just behind the Moana or the ocean.

These are all examples of Hawaiian Fishponds that our ancestors utilized to sustain their main protein food source throughout the evolution of fishponds. Image from ‘Hawaiian Fishpond Study: Islands of O‘ahu, Moloka‘i, and Hawai‘i’ in 1989 by DHM Planners.

Kaheka or Hapunapuna fishponds were tidepools or pools that were fed by springs. They attract fish by either their freshwater outflow or the tides and waves would wash fish into them, and they would be temporarily trapped for people to gather. Loko pu’uone fishponds were naturally made on the shore as sand-dunes would surround and collect pools of brackish (wai kai) water.

Inland freshwater ponds are called loko wai.

Loko Iʻa kalo or taro fishpond was mixed agriculture and fish-trapping system built-in the highland near flooded taro patch. The fish would fertilize the taro and the taro bits and remnants would be fed to the fish along with many micro-organisms naturally growing in the patches. It was a unique way to organize our two main food sources operating as one system!

The two types of fishponds our communities are working to restore are – loko kuapā and loko ʻume iki, the walled ponds. These are fishponds that act like fish traps and hold fish in with sluice gates. The main resource in both these types of ponds are rocks, we call them pohaku.

The two types of fishponds our communities are working to restore are the walled ponds with sluice gates. Photo © Paepae o Heeia and Kinohi Pizarro

These walled ponds were used to create a relatively safe brackish water environment that fish were naturally attracted to. This system used sluice gates to naturally recruit baby fish during low tides. The phytoplankton and freshwater would exit, and the fish would come in. On high tides, the influx of saltwater would attract all the juveniles and bigger fishes to the gates as they naturally want to swim out. These were the tides that the keeper of the pond would gather fish for the day, keep most for a later time but also decided to allow some of the biggest fish back out. The big fish go out to spawn and the cycle continues.

The restoration of Heeia fishpond started to gain momentum once the non-profit organization called Paepae o He’eia started to spearhead the efforts. Photo © Hiilei Kawelo

As part of the organization called Paepae o He’eia, a bunch of friends with amazing connections obtained the lease to restore and conserve He’eia fishpond and focused their efforts on education. Photo © Paepae o Heeia

This fishpond (pictured above) was one of the ponds that saw well-spearheaded efforts in the beginnings of fishpond restoration. There were many caretakers of this pond throughout the years that have taken care of this fishpond in their ways. Later, a non-profit organization called Paepae o He’eia was formed twenty years ago to create momentum. This is where community engagement, education, and culture started to kick in again. I have been working as a Kū Hou Kuapā Technician with Paepae o He’eia.

As part of called Paepae o He’eia, a bunch of friends with amazing connections obtained the lease to restore and conserve this pond and focused their efforts on education. Together they built programs to support education, food production, and restoration.

By 2019 our organization was hosting volunteer groups of 100 people every other weekend. 25,000 people would visit the fishpond every single year. For a restoration effort like this the people’s power, cash revenue, and traffic were needed.

During the restoration, we often start our works in the late afternoon and work the nights, after the participating community members are done with their daily jobs.

This is where I and a lot of others learned cultural practices such as dry-stack masonry. Many cultural protocols for our safety, belief systems, and our betterment, and this place helped to teach so much about where our food comes from.

Sadly, 90 percent of our food is imported to Hawaii. This is sad, especially for our native people. We are getting bought out of our homelands and we do not have land to grow food for our families.

During fishpond restoration works we learned our traditional cultural practices such as dry-stack masonry as pictured here. Photo © Kinohi Pizarro

Some of the biggest challenges encountered through the restoration process of fishponds around Hawaii are invasive species, government policies that make it hard to restore these food systems, poachers, public and community that are against our efforts, lack of funding going into these efforts.

Sadly people not willing to put effort into these food systems because going to the store to buy food is much easier for them. So, education is the key, to begin with, to a reorganization of our food systems based on traditional knowledge and systems.

Also, we need to put a cap on outside people trying to buy land here and focus our economy on food security. Even if our imports went down to 70 percent that would be huge for our tiny island. We need to keep leading the effort of teaching people the importance of these places and keep connecting people to the land again. It is our only hope of survival.

Featured image: Fishpond in Hawai’i. Photo © Ikaika Rogerson