First published on 08/29/2015, and last updated on 03/29/2018

François Depey (Natural Resources Department – Office of the Wet’suwet’en)

A young girl stares at salmon in a pail, freshly caught in the river nearby. Her mother, aunt or grandmother will slice the fish into filets to smoke it. The girl observes. She is still a bit too young to help so for now she is watching and learning. In the background the river runs and tonight its music will put her to sleep. She’ll sleep in the cabin, here on her territory.

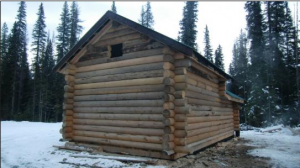

The cabin was built by a crew of ten Wet’suwet’en men over the course of a year. They harvested trees from the forest nearby, then, using a log lathe, turned the logs into wood cylinders of identical diameter. This preparatory work makes building a cabin of simple design look fairly easy. Yet it is still a serious and ambitious project and the story deserves to be told. This cabin story has already inspired other neighbouring indigenous groups and could have the same effect in other places globally.

Although you may not be familiar with what is going on in our part of the world, it may be reminiscent of your own experience as a member of an indigenous group elsewhere. Sub-Arctic indigenous groups, in the context of what is now known as Canada, are referred to as “First Nations” to acknowledge that before the country of Canada was established, there were people living here. They live here still. There are hundreds of First Nations within the colonial nation of Canada, and the Wet’suwet’en is one of them, with its own citizens (members), its own territory, boundaries, language (Wet’suwet’en), governance system and culture.

Despite being acknowledged by the Canadian government since 1997, following a 20-year legal battle, Wet’suwet’en traditional boundaries are not fully recognized. What the government sees as Crown land (i.e. public land under state stewardship) is still claimed as un-ceded territories by the Wet’suwet’en and many other nations within the Province of British Columbia.

The land is considered un-ceded because it fell into colonial government hands not as a consequence of a war or a treaty, but because the traditional peoples welcomed newcomers to their territory. What came with this sense of ownership and entitlement on the part of the Canadian government was a series of familiar colonial tactics: removing indigenous, seasonal nomadic, people from the landscape by imposing sedentary lifestyles along with western culture and religion.

In Canada, First Nations people were moved from their territories and parked in “Indian Reserves”. The reservations are currently run with a federally imposed governance system that only applies to a tiny portion of Wet’suwet’en traditional territories (0.1% of the total area) where, as a result of these relocation policies, the majority of Wet’suwet’en people reside nowadays.

Another method of cultural alienation (some call it a cultural genocide) was a residential school system in which children were forcibly removed from their families and placed in boarding school, often run by Catholic church staff. Children were forbidden to speak their native tongue and grew up without the benefit of family, community or cultural teachings. Incredibly, this campaign, which aimed to “get the Indian out of the child”, was still in operation as late as 1996.

Despite this disturbing history, the Canadian government and the supreme court of Canada still have the arrogance to request proof that First Nations once occupied the territories they claim, and that they continue to occupy them.

Appalling but effective: first you prevent people from using their territory, language and culture for several generations, and then you innocently ask them a question that sounds like: “why don’t you prove to us that you exist and that you have a connection with the territory you claim is yours?” That was for context! It is hard to keep it short and impossible to make it uplifting.

In the 1990s’ the Wet’suwet’en decided to build new cabins where traditional camps were originally located. The cabins were used by members of various family groups (often referred to as clans in the Eurocentric lingo of the settlers and their descendants) and provided an opportunity for people to reconnect with areas of the territory from which they had been displaced. Most importantly, those cabins at the heart of the territory (far from main paved roads and urbanized areas) were used to offer culture camps to younger generations, providing an opportunity for intergenerational exchange and knowledge transfer.

At the beginning of our current decade, Wet’suwet’en leaders agreed to build another generation of cabins. The intent was similar with an expanded vision for objectives:

- provide opportunities for people to spend more time in their territory and build stronger ties with their culture;

- re-occupy portions of the territories that used to be vibrant with culture;

- create construction skills training and work opportunities in the traditional territories for members of the nation; and

- strategically locate cabins in areas that are controversial in terms of development and resource extraction.

Funding was found to hire ten unemployed Wet’suwet’en people as well as experienced supervisors/ trainers. Equipment was purchased, including a portable mill to produce lumber and a log lathe that would generate cabin walls. Wet’suwet’en workers built a construction camp in the territory and some trees were harvested.

The Ministry of Forest dared to inquire whether harvesting permit requests had been filed. The response came in a very blunt and polite way: “Permit! What permit? We are exercising our traditional right of harvesting for cultural purposes”. It put an end to the question. It was clear that neither the province nor the logging and milling industry had ever considered asking for a permit from the Wet’suwet’en before harvesting vast areas of forest on Wet’suwet’en territories (until very recently the most productive lumber mill in the world was located only a short distance from the cabin construction site at the heart of Wet’suwet’en territory).

The crew prefabricated the cabins at the construction site and assembled them on sites chosen by each of the five family groups within their respective territories. The choice of location was what made this project more committed to land management. It was decided that the first cabin would be built by the river that is the ultimate symbol of Wet’suwet’en culture. Kwah is the name for river in Wet’suwet’en. Wedzin means “blue/green clear water”. Wedzin Kwah runs from a lake bearing the same name. Bin is the word for Lake in Wet’suwet’en. Wedzin Bin is a forty-kilometer-long lake fed by rivers coming from four other lakes that, if not as big, are just as wild. Nobody lives there anymore but a dense network of well-marked trails remains an indicator of the human presence that once thrived there. Curiously, neither Wedin Bin nor Kwah show on commercial topographic maps. Instead maps show the name of a priest who once preached his “wisdom” to native indigenous people: “Morice” Lake and River. Wedzin Kwah is also home to four types of salmon. Each spring, juveniles drift by the cabin on their way to the Pacific Ocean. Later in the season, mature salmon make their final journey up the same river to the spawning grounds where they hatched several years earlier. It will be their turn to spawn and die. As they do, their bodies, carried into the forest by eagles and bears, deliver large amounts of ocean nutrients to

the soil and create a uniquely fertile ecosystem, a “salmon forest”. In the past, salmon set the cycle for Wet’suwet’en seasonal migrations. In spring, people left their winter camps located in places such as Wedzin Bin to walk long distances (over 100km) to a canyon downstream where it is easier to catch fish. Nowadays people still catch salmon in that same location.

The decision to build the cabin beside Wedzin Kwah was not only based on scenery and fish abundance. The cabin is located in the proximity of a bridge on which the dirt logging road crosses the river to reach more territory where trees from virgin forests will be harvested. The cabin is strategically located on a proposed oil pipeline route, and controls access over the bridge into pristine territories precisely where several pipeline companies (oil and gas), in various stages in the federal Government permitting process, would like to clear pipeline corridors to the coast.

Wet’suwet’en, like the majority of First Nations on the route, vehemently oppose oil pipelines. The construction of the cabin forced the company to reroute the pipeline a couple of kilometers upstream in order to comply with requirements regarding cultural uses of the land. In recent years, a group of Wet’suwet’en have lived year round in the cabin which has become a site of resistance against unwelcome development.

While pipeline companies still attempt to access the territory using helicopters and other roads, more and more people – Wet’suwet’en, other indigenous nations and non-indigenous allies – have travelled to the cabin to promote Wet’suwet’en ancestral responsibilities to care for the land and water, protecting them for future generations.

In this way, the Wet’suwet’en Nation has succeeded in reaffirming its connections to lands and waters, salmon and other creatures (“our relatives”). It aims to become a major player in decision making and implementation regarding the management of the territory and to lead the way in terms of conservation for the benefit of future generations.

Even if it only offers an opportunity for that young girl, or another child, to get a chance to leave the Reserve to experience the wilder territory, even if only overnight, the cabin initiative will already be on the right track for success.

- Foundations for the cabin with Wet’suwet’en members. Wedzin Kwah in the background © Natural Resources Department OW

- Aerial view of the cabin location (right of the bridge) by Wedzin Kwah (c) M. Ridsale

- The cabin that became the heart of the Unistot’en camp © Natural Resources Department OW

Wet’suwet’en territory – Summer 2015

To get more updates on the cabin that is now used to occupy the territory: www.unistotencamp.com