First published on 02/29/2016, and last updated on 03/29/2018

By: Grazia Borrini-Feyerabend, ICCA Consortium Global Coordinator[1]

In late January 2016, in a cold but rather unusually sunny Cambridge (UK), a bunch of scientists and environmental activists from several continents spent nearly three days discussing a rather abstruse concept: “other effective area-based conservation measures”—OECMs for short—which was thankfully renamed “conserved areas” by the end of the meeting. The result of their deliberation was to be important as it would inspire an IUCN Information Paper for the next SBSTTA of CBD (May 2016) and further CBD Decisions. I participated in a personal capacity, but kept the ICCA Consortium at heart.

The acronym OECMs comes from Aichi Target 11—one of the 20 targets of the CBD Strategic Plan for Biodiversity agreed upon by CBD Parties for the 2011-2020 decade. Spelled out in full, Aichi Target 11 recites: “By 2020, at least 17 per cent of terrestrial and inland water and 10 per cent of coastal and marine areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services, are conserved through effectively and equitably managed, ecologically representative and well connected systems of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures, and integrated into the wider landscapes and seascapes.”

I have been interested in OECMs for quite some time– and I believe I was the first to propose calling them “conserved areas”[2] – because they represent a security valve for areas that are conserved de facto and wish to be recognised for the benefits and values they provide for society, but do not wish to be constrained by fitting the definition of protected area of IUCN,[3] CBD[4] or any relevant government. (Noticeably, the IUCN’s and national definitions of protected areas often diverge, but this does not seem to bother many… counting pears or apples together will do, as long as we count!).

In a political sense, the introduction of “conserved areas” in Aichi Target 11 represents an open recognition of the value of the territories conserved by indigenous peoples, local communities or private owners who refuse to fit and comply with any protected area definition elaborated and adopted outside of the realm of their own self-determination and rights.[5] For me, it also represents the recognition that in no country the formal protected area system comprises all that deserves to be conserved. Pre-existing the protected areas declared and managed by the state or other actors, all landscapes and seascapes include territories, features and relationships that enormously contribute to keeping nature alive. Such “conserved areas” are, so to speak, the “mothers” of protected areas… they are the strong humus over which communities and legislators brought to bear the (relatively recent) protected area institution.

Much of the meeting in Cambridge took an entirely different course. The meeting focused on how IUCN should advise CBD to define “conserved areas” or— more politically important— we were to identify the intrinsic characteristics of conserved areas that would make them count for Aichi Target 11. Should those areas be “effectively managed”? Should they have “conservation of nature” as their primary objective? In case of conflict among diverse objectives of such areas, should “conservation of nature” prevail? How valuable for conservation should they be? And the like… The meeting was a gathering of top level conservationists from all over the world, and their key concern was that countries should not be allow to dilute Aichi Target 11 by listing and counting for the target any sort of “poorly protected” areas (some people mentioned examples such as tree plantations, time-bound fishery closures and municipal water catchments).

The debates during the meeting were frank and interesting. At the end, it seemed to me that most participants continued to see conserved areas as “lesser sisters” of IUCN-defined protected areas. For them, conserved areas need to prove themselves, so to speak, by adhering to much of what is included in the IUCN definition of a protected area and, in particular, to possess an effective management regime and the intent/purpose to conserve nature. In all likelihood, this will be the essence of the Information Paper that the IUCN will submit to the CBD Secretariat.

I had a few main concerns and a clear minority position regarding the interpretation of conserved areas. Concerns: if some indigenous peoples and local communities refuse to fit and comply with the IUCN protected area definition, why would they wish to fit the even-more-demanding definition of a lesser sister? If we care only for areas that are intentionally “dedicated, recognised and managed” for conservation… what do we make of all the territories where conservation takes place in absence of that? Shall we consider those unimportant and abandon them to their destiny?

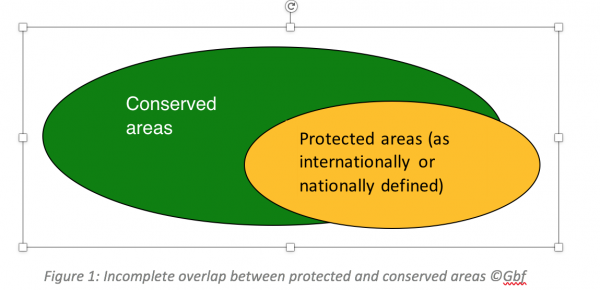

My minority position was as follows: let us take the bull by the horns and define “conserved areas” as all territories that are valuable and conserved de facto. If more precise wordings are desired I would propose: “Conserved areas are natural and modified ecosystems, including significant biodiversity, ecological functions and cultural values that— regardless of recognition, dedication and management—are de facto conserved and/or in a positive conservation trend and likely to maintain it in the long term”. Notably, “regardless” includes full recognition, dedication and intentional management for conservation… as well as nothing of that. So defined, conserved areas have an important degree of overlap with protected areas, but they do not necessarily coincide with them (see Fig 1). The first zone of no overlap regards formally-recognised protected areas that are not conserved de facto (yellow but not green). And the second regards conserved areas that do not fit the IUCN’s, CBD’s and/or national definitions of protected area (green but not yellow).

Examples of areas in the green but not yellow portion above that have a reasonable expectation to sustain conservation in the long-term span commercial hunting operations designed to restore and maintain the habitat of given species; organic farming systems and well-managed watersheds and mangrove forests intended to sustain community livelihoods; military no-go areas; and territories conserved by indigenous peoples who refuse to comply with any specific statement or conditions demanded of them but still secure de facto conservation results. The examples I have just listed lack the conditions of “dedication for conservation”, “recognition for conservation” and “intentionality for conservation”—meaning that these areas were not established, and are not primarily managed, for the conservation of biodiversity. All have other reasons to be, but some are managed in ways that support conservation and are pleased to do so (secondary voluntary conservation) while others truly achieve conservation as a fully unintended consequence[6] (ancillary conservation). Examples of areas where biodiversity may be thriving regardless of management include inaccessible cliffs and other economically uninteresting steep slopes and remote areas where birds and other animals find crucial habitats. All the areas just mentioned do not fit the IUCN definition of protected areas. They may also not be included in the national protected area system of the country at stake. But they do contribute to conservation and it may be reasonable to imagine that this could remain true in the long term.

I believe that a country reporting to CBD about progress towards Aichi Target 11 should have a base count of all areas that contribute to conservation of nature— including both protected and conserved areas— and that conserved areas should include secondary voluntary conservation, ancillary conservation as well as areas conserved simply because they are un-managed and left alone. This “base count” would be valuable per se, even if, for the Aichi Target, it may need to be reported with a correcting factor that takes into account the target’s preamble, namely that areas have to have value (ecologically representative, have special importance for biodiversity, are crucial for connectivity) and be secured (effectively and equitably governed[7] and managed, well connected and integrated). A definition of conserved areas as all territories conserved de facto coupled with a strong interpretation of Aichi Target 11 (“we count only what has value and is secured”) would be logical and robust. It would also have the merit of highlighting the efforts of all those rightholders who sustain the opportunity costs of maintaining undisturbed and unexploited those areas that are important for conservation but are not necessarily “recognised, dedicated or managed for it”.[8] It would, in particular, highlight areas that are not large, visible and impressive, but dispersed, difficult to identify, organically shaped and changing (e.g. a river‘s delta) and/or consciously destined to fit the specific needs of the social actors governing them… but still essential for many conservation results—and for ecological connectivity first and foremost! Lastly, a strong interpretation of Aichi Target 11 (“we count only what has value and is secured”) should apply to “conserved areas” but also to “protected areas”, which should prompt important in-depth reviews of national conservation systems.

To be frank, some possible problems lie ahead if we embrace my minority position. First, finding out how to define and monitor all areas that are “conserved de facto” is challenging, even for professional conservationists. Having to do this for an entire country is definitely onerous. Second, the percentages included in Aichi Target 11 were agreed upon with a reference point to existing protected areas (usually only government-managed protected areas) and not to conserved areas. The unspoken aim was to “extend the coverage of official protected areas as much as politically feasible”. The 17% and 10% values included in Aichi Target 11 may thus be figures with tenuous reference to what is really needed to maintain our planet in some form of ecological balance. In other words, clarifying the percent value of what we need to keep alive of the “conserved areas” in a given country… is truly still an open question.[9]

Heading to the train station after the Cambridge meeting I could not but wonder whether— more practical than any disquisition on “what counts for Aichi Target 11”— is not the question of “what happens to a territory that has been counted”. In my view both the “protected areas” and “conserved areas” that a country will be allowed to “count” towards Aichi Target 11 should be offered stronger security and protection from many of the over-powering phenomena (mining, oil and gas concessions; large infrastructures; palm oil, sugarcane, eucalyptus and other biodiversity-desert monocultures; intensive grazing; industrial pollution; urbanisation…) that currently spell out the dismay and impoverishment of nature all over the world. As many of the areas at risk have been governed, managed and conserved for centuries by indigenous peoples and local communities, it would make enormous sense to take effective steps to support and secure their claims to collective land rights and security from undesired destructive developments. For the moment, however, this is far from being a clear consequence of counting “conserved areas” for Aichi Target 11… neither as mothers, nor as lesser sisters.

- Women and forest in Odissa, India. © Jason Taylor

- The Bajo Lempa community, El Salvador, is fighting to preserve its mangrove environment and food sovereignty threatened by a large-scale tourism development © Jason Taylor

[1] Grazia would like to thank Ro Hill, Peter Bridgewater, Taghi Farvar, Barbara Lausche and Barbara Lang to their positive and constructive comments to an earlier version of this article.

[2] Borrini-Feyerabend, G. and Hill, R. (2015) ‘Governance for the conservation of nature’, in G. L. Worboys, M. Lockwood, A. Kothari, S. Feary and I. Pulsford (eds) Protected Area Governance and Management, pp. 169–206, ANU Press, Canberra.

[3] In particular they do not wish to be “recognised”, “dedicated” and “managed” for the conservation of nature, and they do not wish to maintain that, in case of conflict, “conservation” is their undisputed primary objective.

[4] In this case, they do not wish to be “designated” or “regulated and managed”.

[5] This remains true even when, as today, many indigenous peoples declare their own ICCAs and voluntarily adhere to conservation goals (M. Taghi Farvar, personal communication, 2016).

[6] For instance, the area of Chernobyl, abandoned because of radioactive pollution, is currently a refuge for biodiversity.

[7] I add the term “governed”, which is missing in Aichi Target 11, as not including it was a widely recognised oversight.

[8] Some conservationists even maintain that much of what goes under the name of “management for the purpose of conservation” is actually damaging, and should be avoided… another clear minority position!

[9] Ro Hill notes that the “Planetary Boundaries” assessments (Rockstrom, J. et al., “A safe operating space for humanity”, Nature, vol. 461: 472-475, 2009) points at the fact that we have already crossed thresholds for biodiversity and suggest that the answer is simple: we need to keep all remaining working habitats, about 55% of Earth’s land surface, and even add to that value by restoring many degraded ecosystems.