First published on 11/21/2017, and last updated on 09/17/2020

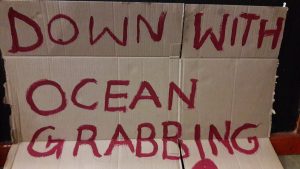

OUR OCEANS AND OUR COASTS ARE NOT FOR SALE! # Down with ocean grabbing! Protect our seas! Dignity for all! Down with a top down approach!

These are the messages coming from small-scale fishing and coastal communities in South Africa who are voicing their concerns about the government’s approach to Marine Spatial Planning and the exploitation of marine and ocean resources.

On November 21, 2017, Masifundise together with Coastal Links, a national umbrella network of small-scale fishing communities, hosted two High Level Policy Roundtables with government officials from the Department of Environment, Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, provincial and local government as well as conservation agencies and other organisations in order to voice their concerns about the extractive nature of Operation Phakisa. On World Fisheries Day on the 21 November fishers in the Eastern Cape together with their social movement partners hosted a protest through the streets of East London.

Amidst news reports this week from KZN that the government has given the green light for the drilling of oil off the KZN coastline, and that 98% of the Exclusive Economic Zone has already been leased out for oil and gas exploration, small-scale fishers are drawing attention to the failure of the DAFF and DEA to respect their rights and the irony of the situation they find themselves in where government officials are promising them thousands of jobs through Operation Phakisa, but has yet to secure their small-scale fishing livelihoods, something they have repeatedly promised since the Equality Court ordered the Minister to do this in 2007.

Background on Operation Phakisa and small-scale fishers’ concerns

In 2014 President Zuma launched Operation Phakisa. Phakisa means ‘hurry up’ in Sesotho and with this multi-sectoral programme, the government aims to fast-track the exploitation of what they refer to as the ‘ocean economy’. Operation Phakisa is linked to the National Development Plan’s goals of creating jobs and reducing poverty for the country. Drawing on ideas gained from Malaysia, President Zuma announced that South Africa would embark on this ambitious programme with a view to rescuing the South African economy through large-scale industrial development programmes that draw on the oceans and its resources. He said that Phakisa aims to “unlock the potential of the ocean” and promote “multiple socio-economic benefits”.

This turn towards the oceans of the earth, described as the ‘blue economy’ is not a new one or unique to South Africa. Globally there has been increasing focus on the oceans as a means to continue growth in world economies. The term ‘blue economy’ has been used to describe this form of economic exploitation that depends on the ocean resources for this growth despite the fact that these are largely non-renewable resources such as minerals, oil and gas. Promoters of this approach often remind us that the planet’s oceans make up over 70% of the planet.

Operation Phakisa Ocean Economy has four primary components:

- Offshore Oil and Gas Mining;

- Marine Transport;

- Aquaculture; and

- Marine protection services and ocean governance.

In addition, Marine clusters have been launched to add a focus on Small Harbours and Tourism.

On the 6th of October 2017 the President reported that “a lot of progress has been made” in the first three years of Phaksia. He announced that the programme has unlocked billions of rand in investments and has created 6500 jobs. There has been considerable infrastructure development, in anticipation of considerable activities in the oil and gas sector and in promoting South Africa’ a leader in terms of its Ports and marine transport and manufacturing capabilities. In the Offshore Oil and Gas Focus Area, fourteen exploration rights, six production rights and two technical cooperation permits have been issued.

The Department of Environment (DEA) has been appointed the lead agent in Operation Phakisa and to coordinate planning and optimise sustainable economic growth and development of the ocean space the DEA has developed the Marine Spatial Planning Bill. During August of this year public hearings were hosted around the country to discuss this bill. In 2015 the DEA announced the gazetting of 22 Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) as part of Operation Phakisa for public comment and the regulations for these MPAs are now being finalised. President Zuma noted in his report that the MPAs will serve as nurseries for fisheries.

The Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (DAFF) has launched a far-reaching aquaculture development plan which includes the establishment of Aquaculture Development Zones and planning for numerous aquaculture projects is underway in all four coastal provinces.

What the report from the President failed to note is that there has been widespread expression of concern and protest about Operation Phakisa from small-scale fishers, coastal communities, marine resource users and environmental organisations who have voiced their opposition to the crude, extractive nature of Phakisa and the exploitation of the ocean which flies in the face of many of the international and regional laws and conventions to which South Africa is a signatory. In particular, small-scale fishing communities and other stakeholders are concerned about the destructive impact that this industrial exploitation of the ocean and marine resources will have on the marine life which they depend on for their livelihoods.

In Durban the South Durban Community Environmental Alliance (SDCEA) and environmental NGO Groundwork have voiced their grave concern regarding the oil and gas drilling planned under Phakisa. They note that the government plans to extract 9 billion barrels of oil from the ocean. The Oil and Gas component of Phakisa intends to drill 30 exploration wells in the next ten years. SDCEA and Groundwork point out the contradictions between Operation Phakisa and South Africa’s climate change commitments to move towards a low carbon economy and the reduction of carbon emissions (Chademana and Joseph October 2017 Natal Mecury). In the face of looming seismic testing and oil drilling, small-scale fishers in Durban launched a campaign in June to demand ‘Fish not Oil’ and to raise public awareness of the environmental impacts of marine mining as well as the potential impacts on their own livelihoods.

In 2012 the DAFF gazetted a Policy for Small-scale Fisheries and in 2014 the Marine Living Resources Act was amended to recognise the rights of small-scale fishing communities for the first time. This followed an order of the Equality Court in 2007 that demanded that the Minister responsible for fisheries consider the socio-economic rights of traditional fishers. Up until then these fishers had been left out of the legislative and policy reforms post apartheid. The Coastal Links small-scale fishing communities of KZN were extremely frustrated when the draft regulations for the Operation Phakisa 22 MPAs were gazetted and all but one failed to accommodate small-scale fisheries. On the contrary, several of these MPAs would restrict them further. They also note that the draft Integrated Management Plan for the iSimangaliso World Heritage site released in 2016 ignored their rights. They are puzzled as to why the new round of Integrated Development Plans (IDPs) at local municipal level in KZN fail to accommodate them or identify their needs despite the imminent implementation of the Policy for Small-scale Fisheries. These fishers are extremely concerned that even though their rights to food security and their livelihoods have yet to be recognised, Phakisa developments are fast gaining priority and are going to squeeze them out of the ocean space. They say that they are once again falling through the net, their rights are being ignored and their voices are not heard. The fishers note that most of their communities have used and depended on marine resources since time immemorial. They have customary rights to these resources and acknowledge their responsibility as custodians of these resources to ensure that they are used sustainably and for the benefit of the next generations.