Asmara is an elder and fisher in the coastal village of Mumiang in Sabah, Malaysia. This story follows Asmara’s fishing life and the successes of his Suluk Indigenous People in establishing and governing a locally managed marine area in the Kinabatangan River estuary

First published on 08/10/2022, and last updated on 06/18/2025

By Neville Yapp with LEAP – Land Empowerment Animals People (ICCA Consortium Member),

Persatuan Komuniti Kampung Mumiang, and

Forever Sabah

In the mangroves of the Kinabatangan estuary, fluorescent lights illuminate the river banks along the main river as people wake up to the call for Fajr prayer. The birds have started chirping for a while. Soon, the sharp rays of the hot tropical sun pierce through the misty morning dew. Schools of mullet and archerfish wander under the stilt houses built over the river channels.

Asmara eagerly gets into his boat, sets up his rustic boat engine singlehandedly, and takes off. He lays out the net in his favorite spot some hundred meters from his house in Mumiang village’s main river channel.

On most days, Asmara returns home with a few snappers, croakers, and shads after two hours of fishing. He sells fish of suitable sizes to community-owned cold storage. The smaller ones are for the family; he keeps a few for meals and cleans the rest for drying.

For Asmara, this is his only way of sustaining his family. He is 75 years old and can no longer toil on the open seas for the lucrative yet uncertain tiger prawns destined for the tourists at famous seafood restaurants in the nearby town of Sandakan.

The people of the ocean-current

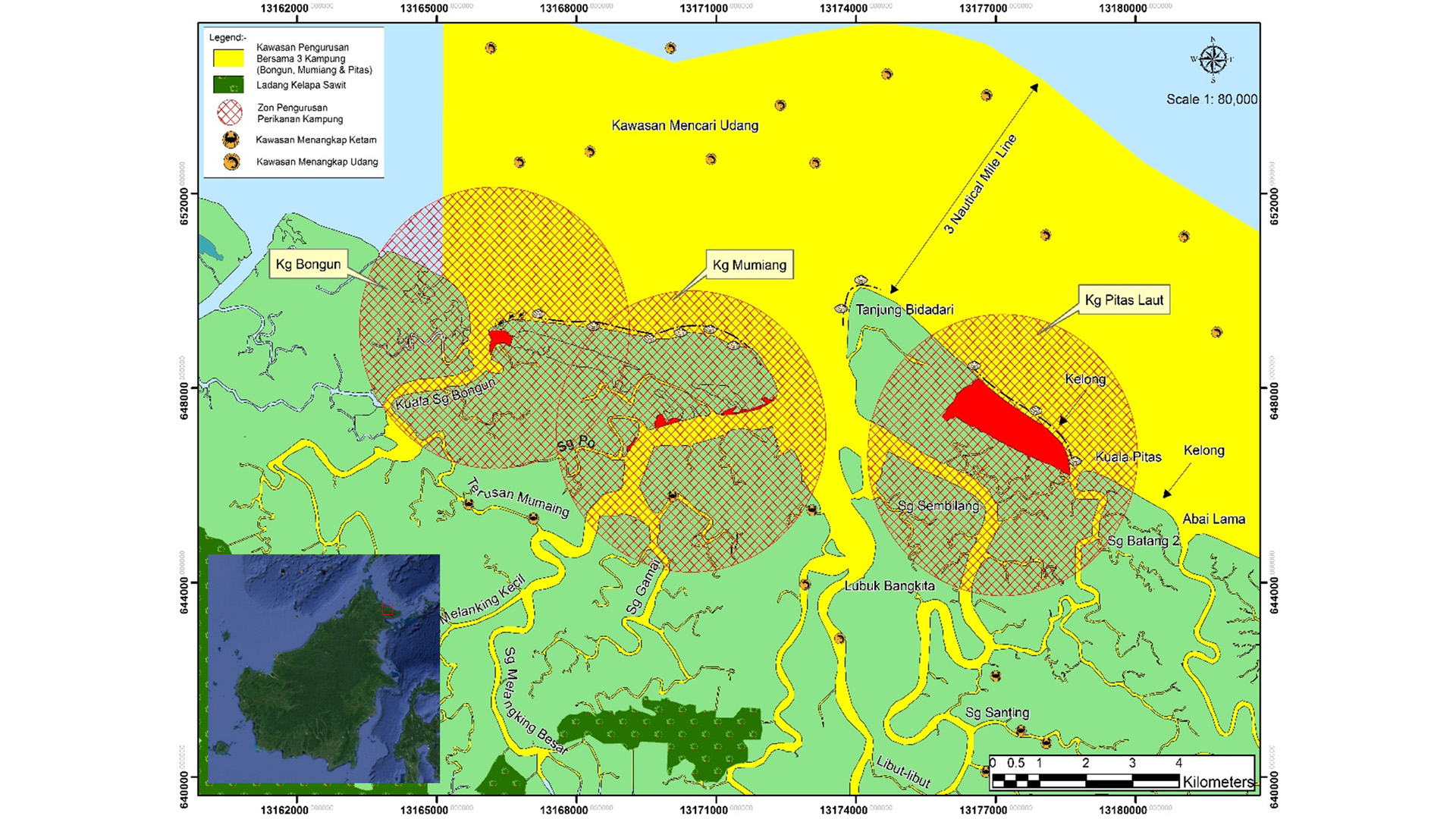

The Suluk people are the principal inhabitants of Mumiang. Theirs is a traditional fishing village situated at the mouth of the Kinabatangan River on Sabah’s east coast in Malaysian Borneo. The Mumiang’s coastal territory of life comprises 300 km² of mangrove-rich estuary inherited from their ancestors. This territory is lying within what is now Malaysia’s largest “wetland of international importance.”

‘Our sustenance will be more blessed if we care for the environment. If we take care of nature, nature will also take care of us and bring us more returns.’

— Asmara, Elder from Mumiang village

Suluks are one of the many Indigenous Peoples in the Malay Archipelago. Life in many of these communities is more intertwined with the ocean than land. But still, through colonialism, their territories have become divided by modern states that rule from dry land.

Another name for the Suluk people is the Tausug. Tau means human or people, and Sug (alternatively spelled Sulug or Suluk) means ocean currents. In Malaysia, these people call themselves Suluk to differentiate from the Tausug, who are now considered native to the modern state of the Philippines.

These villages live by the Islamic lunar calendar to guide their daily lives. This calendar tracks the moon’s cycle, which is reflected in the tides and fish behavior.

Asmara’s wisdom: Indigenous practices and the rhythms of nature

Asmara does not require a tides chart. He knows the lunar month and cycle by heart and thus the state of the water on any given day. From about the fifth day after the new moon to the twelfth and leading into the first quarter, Asmara’s fishing strategies take advantage of slower currents and lower tides.

During the full moon, the higher tides mean fish will spread out inside the mangroves, and strong currents mean fishing baits and gill nets will drift away. This moonlit part of the lunar month is reserved for sewing nets and non-fishing activities. By aligning his livelihood practices to the rhythms of his aquatic territory, Asmara lives as the king of his own life.

Asmara is also an expert at observing the winds and adjusting how he fishes in the changing seasons. The Angin Utara (Northeast Monsoon), occurring from October to February, brings floodwater rich in upstream nutrients into a delicate balance.

Upon reaching the coastal areas, these nutrients support plankton blooms that, in turn, catapult mass-spawning events towards the end of the floods. Asmara and his neighbors embrace these annual floods, even as heavy rain and rough seas mean it is a time for the communities to rest.

But floods also flush down giant freshwater prawns and bring them hundreds of kilometers downstream to the estuary. According to Asmara, the yearly influx of freshwater into the tidal creeks also helps the village’s open-water fish pens. He says that fish in the pens can cleanse their gills and bodies from parasites with the freshwater rushing to the sea. So the villagers do not need chemical pesticides to raise fish in the pens.

The arrival of the Angin Selatan (Southwest Monsoon) brings a sense of renewal. The calmer seas and transparent waters in the delta mean a new season ideal for hook and line fishing and traditional fish traps. It is also a time to visit relatives, arrange marriages and festivals, and earn from tourism and crafts while taking advantage of the daily commute to the city to deliver fresh fish for sale.

Asmara is always ready to share the many taboos and good manners that must be observed when fishing to avoid danger and make a good catch, including the correct behavior before entering the mangrove forest to collect other resources for subsistence. These are among the many practices and beliefs held by most people in the Kinabatangan and Segama delta. These practices and beliefs signify their respect for the places that have provided for their needs for generations.

Changes in the tide country

However, things are changing. Asmara feels people do not respect the seas as much as they used to. People are forgetting the traditional ways and are shifting into commercial approaches, using less environmentally friendly fishing gear to make ends meet. There is also more competition as fishers from other areas move in to exploit the remaining productive regions of the Kinabatangan and Segama delta, creating tension with the Indigenous communities.

Asmara says that the environment has also changed. The upstream opening of forest and palm oil plantations has disrupted many tributaries’ fragile nitrogen cycle balance. Too many nutrients, including agrochemicals, causes mass fish kills. River water is not as fertile as before. Sometimes the Northeast monsoon fails, meaning no floods and no prawn season; this has happened several times in the last twenty years.

Asmara has a poetic way of describing the decreasing fisheries productivity. He says, ‘the Berkat (blessings) from our arduous labor are less than before.’ He shared how people back in the day could afford to make the Hajj to Mecca just from fishing incomes. He reminisced with excitement how a single throw of a cast net could then fill up a big bucket with prawns.

Ten times as much effort is now required to catch the same amount with cast nets. This is why many people have started using three-layered nylon nets, a gear type in which many juveniles get caught, reducing the number of juveniles able to grow to mature sizes and spawn.

Governing and managing Ha’alupan Bai (waters in front of our village)

Since the pandemic’s onset, with the support of locally trained facilitators, the community in Mumiang has been organizing grassroots discussions and peer learning exchanges about Indigenous and Community Conserved Areas (ICCA) and Locally Managed Marine Areas (LMMAs) using the self-strengthening process. This process led to the development of a fisheries governance protocol, launched in late 2021 through a ritual and recitals of verses from the Quran led by the village Imam, binding the community together.

The fisheries governance protocol is referred to as Ha’alupan Bai (waters in front of our village) and is inspired by the knowledge of Renggas.

Renggas are underwater structures found along coastal mangrove estuarine areas and tidal creeks. They consist of mangrove roots, sunken trees, or rocky surfaces. Like coral reefs, these underwater structures are habitats for marine life. The Suluk people are experts at replicating these structures to attract schools of fish.

Renggas is usually deployed during the Southwest monsoon when water is more transparent. They are traditionally built by cutting and sinking mangroves trees in preferred depths and left for a period to attract schooling fish. However, local authorities view this method as unsustainable, and many communities have been discouraged from continuing the practice.

The fisheries governance protocol is an effort by the community to recover fish abundance at a manageable scale by designating several small areas along the main river channel as no-take zones and enriching them with Renggas – fish aggregating structures.

With a radius of fifty meters, this structure shelters juveniles and mature fish sizes and encourages the schooling of fish around these structures. This fishery governance protocol aims to advance the shared governance approach jointly with the Sabah Forestry Department.

Through consultations, the community now targets the increased abundance of all snapper and grouper species common to the area, including the famed Bornean Black Snapper (Lutjanus goldiei). These structures also reduce the indiscriminate use of gill nets which helps other species such as the Indian Threadfin (Leptomelanosoma indicum), which has been heavily fished in the last two decades. Asmara is an active supporter of the process and has contributed to a rich pool of traditional knowledge alongside other knowledge holders.

Access to mobile technology has increased significantly over the years in the area. The fishers of Mumiang have been recording their catches using the Open Data Kit installed on their mobile devices to see changes in their fishery. Once the sites reopen, the collected data will be used for the ongoing management of the LMMA.

Alternative livelihood development is key to the LMMA strategy of Mumiang as it aims to diversify income sources and reduce fishing pressure. With support from local partners, the community has set up a cold storage and processing center, enabling the community to diversify fish products and cope with the fishery market disruption caused by the pandemic.

Communities in Mumiang and other territories of life in the lower Kinabatangan and Segama wetlands have been organizing the self-strengthening process since 2015 with support from Land Empowerment Animals People Trust, a member of the ICCA Consortium.

Since then, the community in Mumiang has mapped and documented their territory of life, advanced livelihoods, and community organizing skills, including environmental monitoring to raise local capacities to effectively engage in the shared governance of the area with state agencies. Since 2020, the ICCA Consortium’s Marine, Coastal, and Island Territories of Life Initiative has supported this ongoing program, along with the UNDP-Orang Asal Microgrant Facility (UNDP OA-MGF) conservation-based livelihoods, and Yayasan Hasanah in the village of Mumiang.