ICCA Consortium co-founder Grazia Borrini-Feyerabend shares broad trends over the past 30 years and a warning about what may come

First published on 11/19/2021

By Grazia Borrini-Feyerabend (ICCA Consortium Council of Elders)

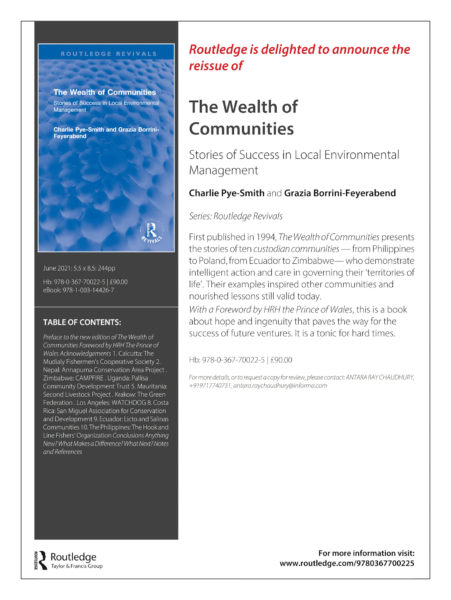

Possibly because we live in them and observe them closely, recent decades seem to have accelerated change in all sorts of fields. We seem to make fresh discoveries all the time, and we get excited as they readily promise to solve our ills. It came to me as a sort of ‘surprise’, then, to realize for how long the value of grassroots initiatives for conservation has been known. The volume The Wealth of Communities, recently re-issued in the Routledge Revival Series, advocates for the appropriate recognition and support of custodian communities willing to govern their territories of life.

That the book was written about thirty years ago offers an occasion to ponder and wonder. Yes, the terminology has slightly changed (back then we called it ‘primary environmental care’), but the idea of focusing on empowered communities as crucial actors in sustainable livelihoods and conservation was right there. And it was not at the fringes. We had succeeded in including it in Agenda 21 – the main UN strategic approach for the 21st century. It was discussed at a high level in national and international settings. It made good, well-demonstrated sense. It would pull together people to keep advocating in the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, UN Convention on Biological Diversity and beyond. Years later, it would ground the birth of the ICCA Consortium.

Yet, around the mid-1990s, a slow backlash was already visible. Stimulated by the new financial resources pouring into conservation, large-scale, expert-run initiatives became de rigueur. Conservation organizations mutated into consultant enterprises. Local initiatives became ‘futile’ unless they could be replicated and multiplied on a grandiose scale. The idea that conservation needed money— the more the better— seemed to trample everything else. Honest and humble communities wanting to go on with their lives, in nature and culture, protected from the excesses of extractive, financial and military industries… were seen by some as ‘irrelevant’. We lost many fights, since then, and we should be wary today. As ‘conservation by Indigenous Peoples and local communities’ becomes fashionable again, the financial resources of the new ‘nature asset class’ are ready to welcome it with open arms. Hopefully, people remember, learn, move on. Rather than falling into the same traps, the leaders of today will pre-empt them. They will focus on what is truly important – for them and for the movement.