During the latest session of the FAO’s Committee on Agriculture, Nahid Naghizadeh delivered a side event presentation on the importance of mobility and nomadic and pastoral peoples in managing biodiversity and food systems, drawing from deep experience in Iran

First published on 07/29/2022

By Nahid Naghizadeh, CENESTA (ICCA Consortium Member)

The mobility and seasonal migration of pastoralists is the most effective strategy and explicit method to protect and restore ecosystems. Mobile pastoralists often produce food and ecological services and are the only significant economic contributors in the world’s poorest regions. The migratory practices of Indigenous nomadic pastoralists are almost always de facto nature conservation strategies. In addition, pastoralists’ mobility is a cohesive and unified social, economic, and ecological system that significantly contributes to food security at various levels and provides an opportunity for the natural landscapes and ecosystems to restore and revitalize their biodiversity while adapting to the territory’ climatic conditions. Biodiversity provides a fundamental base for pastoralists’ livelihoods and Indigenous food production systems. Based on their traditional, Indigenous and local knowledge, pastoralists apply the required monitoring and predictions and take the necessary conservation actions to reduce pressure on their ecosystems.

Among the strategies that pastoralists adopt throughout the year are actions such as:

- adjusting the date of migration and length of settlement in summering and wintering grounds;

- understanding the quality and quantity of rangelands vegetation for assessing the carrying capacity of destination rangelands before migration;

- traditional practices for conserving vegetation through rotational grazing system in their territories, sowing, and plant regeneration;

- fertilizing the soil using animal manure, traditional rangeland irrigation systems to enrich vegetation;

- purchasing secondary fodder and renting the farmland post-crop;

- avoiding grazing in poor rangelands; and

- building small stone dams to prevent soil erosion in slopes and principled and balanced harvesting of wild plants and avoiding root detachment.

READ MORE: “Chahdegal: The continuous effort to conserve territories of life in Iran”

Challenges:

The evidence show that the benefits of pastoralists’ socio-economic and ecological contributions are not well included in statistics. The absence of these true values fuels the marginalisation of pastoralists and encourages policies that erode sufficient support for pastoralists in policy dialogues.

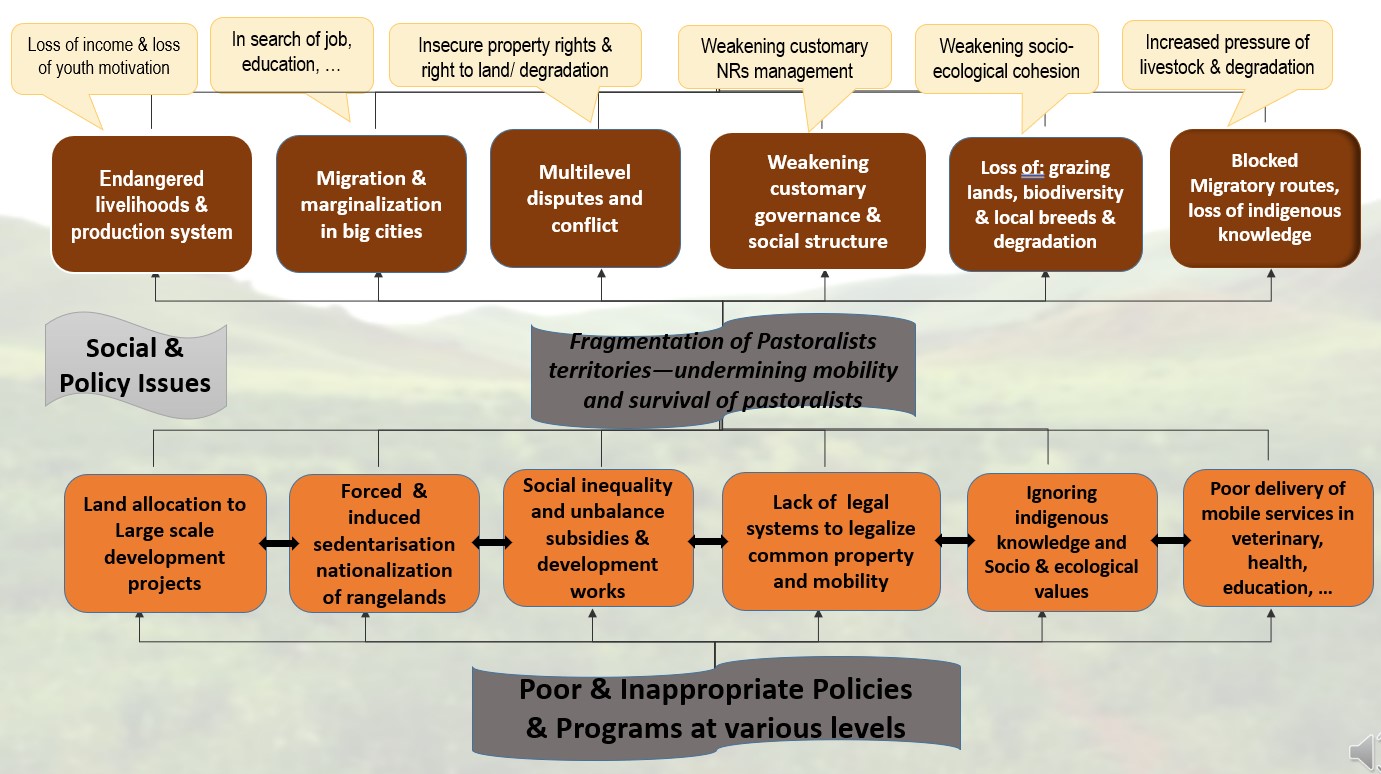

Mobile pastoralists face various challenges in conservation, sustainable use, restoration of rangelands, protection of their biological and cultural diversity, and resilience features within their territories of life. In the recent past, their customary governance systems have faced issues threatening their very existence. Chief among these threats is the induced weakening of the social governance systems and the resultant fragmentation of pastoralists’ territories of life due to generations of marginalisation and exclusion from decision-making processes that affect them, dispossession from territories, and cultural practices. These have, in turn, resulted in various social issues and erosion of the socio-ecological integrity of pastoralists territories.

In an overall picture, this figure shows how mobile pastoralists increasingly are under threat from legal, economic, social, and political disincentives. It shows that the ultimate drivers of rangeland degradation and loss of biodiversity are typically associated with policies, socio-economic changes, or interactions of socio-economic and governance factors with climatic stresses, such as drought. In recent years, drought has been the most important climatic shock for pastoralists, which has caused the extinction of some range plant species, weakening of the livestock, depletion of water resources, reduced vegetation, reduced period of nomads’ settlement in summering or wintering grounds, and therefore more use of secondary fodder and increased conflicts with the villagers on water resources.

In addition to these challenges, since mid-2021, the profitability of the nomads’ food system has declined extremely. At present, there is an obvious imbalance between the level of income of tribal communities and the high costs of fodder and other living costs. If the high price of fodder remains stable and the government doesn’t take strategic action to raise and fix a reasonable price for the pastoralists’ live animals, pastoral communities will not be able to sustain themselves economically and might even go bankrupt.

In a nutshell, the poor and inappropriate policies and programmes and climatic shocks are the main causes of the fragmentation of pastoralists’ territories and loss of biodiversity—undermining their mobility and survival and, in turn, threatening their Indigenous food systems and livelihoods.

Key messages:

Indeed, the trends of various experiences of the past 60 years in Iran have shown that relevant policies and programs on pastoral communities were not and would not be succeeded without considering mobile pastoralists’ key role before any decision-making and project implementations. However, it is crucial to put in place supporting policies based on various and specific socio-economic and ecological characteristics of mobile pastoralists in different regions and nations, including by:

- Recognising pastoralists’ territories of life, recognising and realising the secure and sustainable right to land and its resources, and recognising their customary governance systems over their territories. This could be through stopping fragmentation of their territories and developing community-based restoration and restitution plans, benefiting natural ecosystems as well as the socio-economic situation of pastoralists.

- Establishing binding strong supporting policies and resources to enhance the resilience and mobility features of pastoralists on environmental tensions and taking immediate urgent actions to save the endangered livelihoods and territories of pastoralists in current crisis due to land use change, drought and high cost of fodder.

- Supporting and encouraging pastoralists youth to take responsibility for preserving, sustainable use, and restoration of their territories and promoting their Indigenous food systems, from sustainable production to consumption (production, packaging, labelling, marketing, and sales).

In the end, I hope all relevant international policy platforms and multilateral instruments such as the three Rio Conventions and UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, UN resolutions such as the International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists (supported by 102 countries and 308 organisations as a global movement and mechanism to raise awareness and fill knowledge gaps about the value of healthy rangelands and sustainable pastoralism), the Dana Declaration and so on, will create an enabling environment to support and conserve the bio-cultural diversity of pastoralists, rangelands and their Indigenous food production systems toward achieving sustainable production and consumption, food security and food sovereignty at various levels.