Territories of Life: 2021 Report shows the undeniable role of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in ensuring a healthy planet for all and the urgent actions required to support them

The

Evidence

Base

Territories of Life: 2021 Report is a local-to-global analysis of territories and areas conserved by Indigenous Peoples and local communities (sometimes abbreviated as “ICCAs” or more simply as “territories of life”).

This multi-scale approach weaves diverse perspectives, insights, and new findings about the grassroots global phenomenon of territories of life while also creating space for nuance and complexity. Overall, the report adds to a growing body of literature on the incontrovertible role of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in ensuring a healthy planet for all and the urgent actions required to support them. Explore the different components of the report and the key findings, conclusions, and recommendations below.

Executive

summary

Territories

National and regional analyses

Global analysis

Overall key findings of Territories of Life: 2021 Report

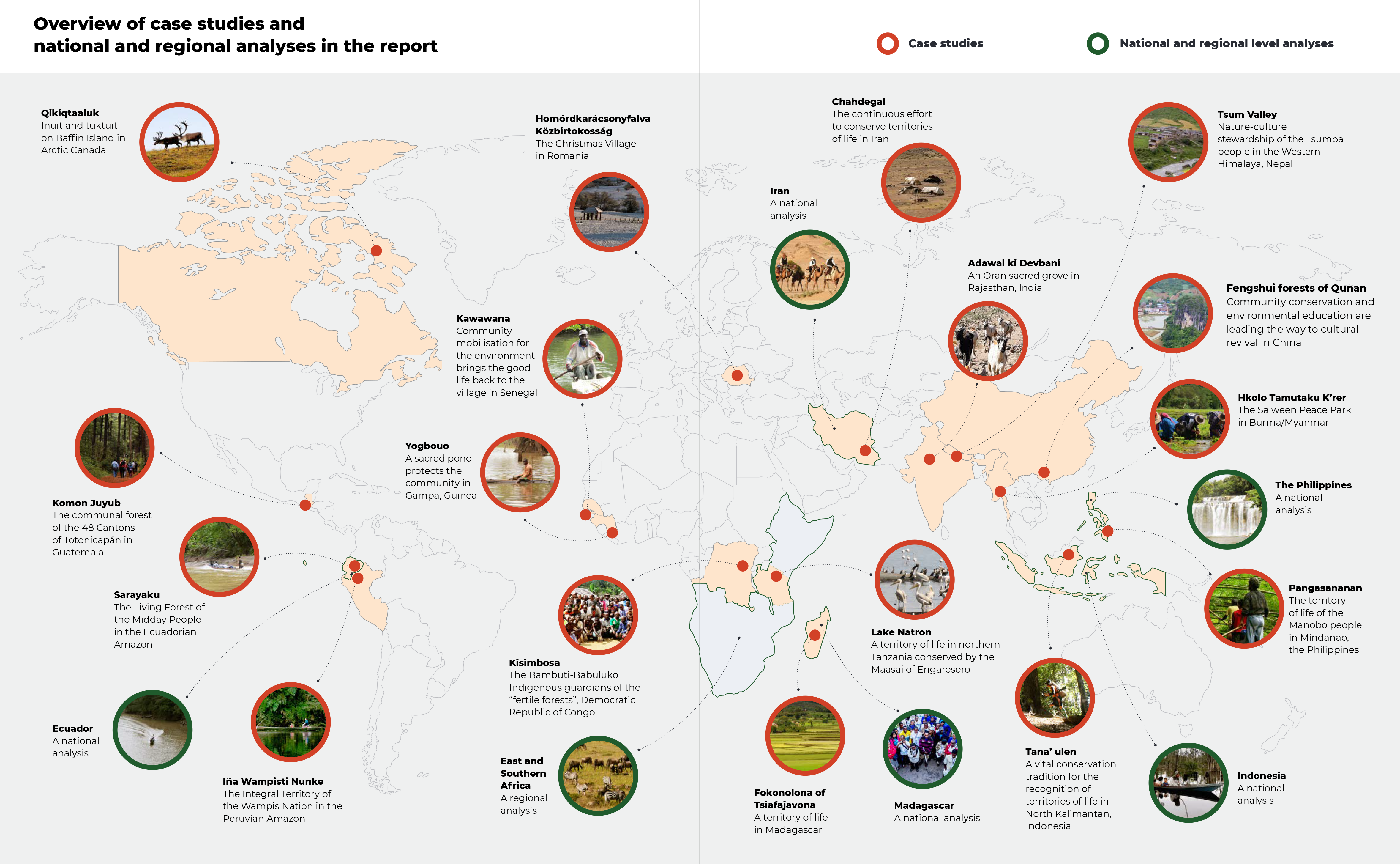

Drawing from the 17 case studies of territories of life, six national and regional analyses, and the global spatial analysis co-published with UNEP-WCMC, the overall key findings of the 2021 report are as follows:

Indigenous Peoples and local communities play an outsized role in the governance, conservation, and sustainable use of the world’s biodiversity and nature. They actively protect and conserve an astounding diversity of globally relevant species, habitats, and ecosystems, providing the basis for clean water and air, healthy food, and livelihoods for people far beyond their boundaries.

Indigenous Peoples’ and local communities’ extensive contributions to a healthy planet are rooted in their cultures and collective lands and territories – in essence, the deep relationships between their identities, governance systems, and the other species and spiritual beings with whom they co-exist. Thus, they also contribute significantly to the world’s cultural, linguistic, and tangible and intangible heritage.

The global spatial analysis shows that Indigenous Peoples and local communities are the de facto custodians of many states and privately governed protected and conserved areas. They are also conserving a significant proportion of lands and nature outside of such areas. However, the mainstream conservation sector has a historical and continuing legacy of contestation for Indigenous peoples and local communities, depending on how their rights, governance systems, and ways of life are recognized and respected. This poses both a challenge and an opportunity for future directions of local-to-global conservation efforts.

Indigenous Peoples and local communities are on the frontlines of resisting the main industrial drivers of global biodiversity loss and climate breakdown. They often face retribution and violence for doing so. Along with other challenges, these multiple stressors can have cumulative and compounded effects on Indigenous Peoples and local communities, posing longer-term threats to their lives, cultures, and resilience. However, they resist and respond to these threats in diverse ways.

Even in the face of immense threats, Indigenous Peoples and local communities have extraordinary resilience and determination to maintain their dignity and the integrity of their territories and areas. They are adapting to rapidly changing contexts and using diverse strategies to secure their rights, collective lands, and territories of life. Although not without setbacks, they have made key advances and continue to pursue self-determination, self-governance, peace, and sustainability.

Key findings of the global spatial analysis co-published with UNEP-WCMC

Co-published by UNEP-WCMC and the ICCA Consortium, the global spatial analysis is the most comprehensive analysis of the estimated extent of territories and areas conserved by Indigenous Peoples and local communities (referred to in this analysis as “potential ICCAs”). The key findings of this global analysis are as follows.

Indigenous peoples and local communities play an outsized role in the governance, conservation, and sustainable use of the world’s lands and biodiversity.

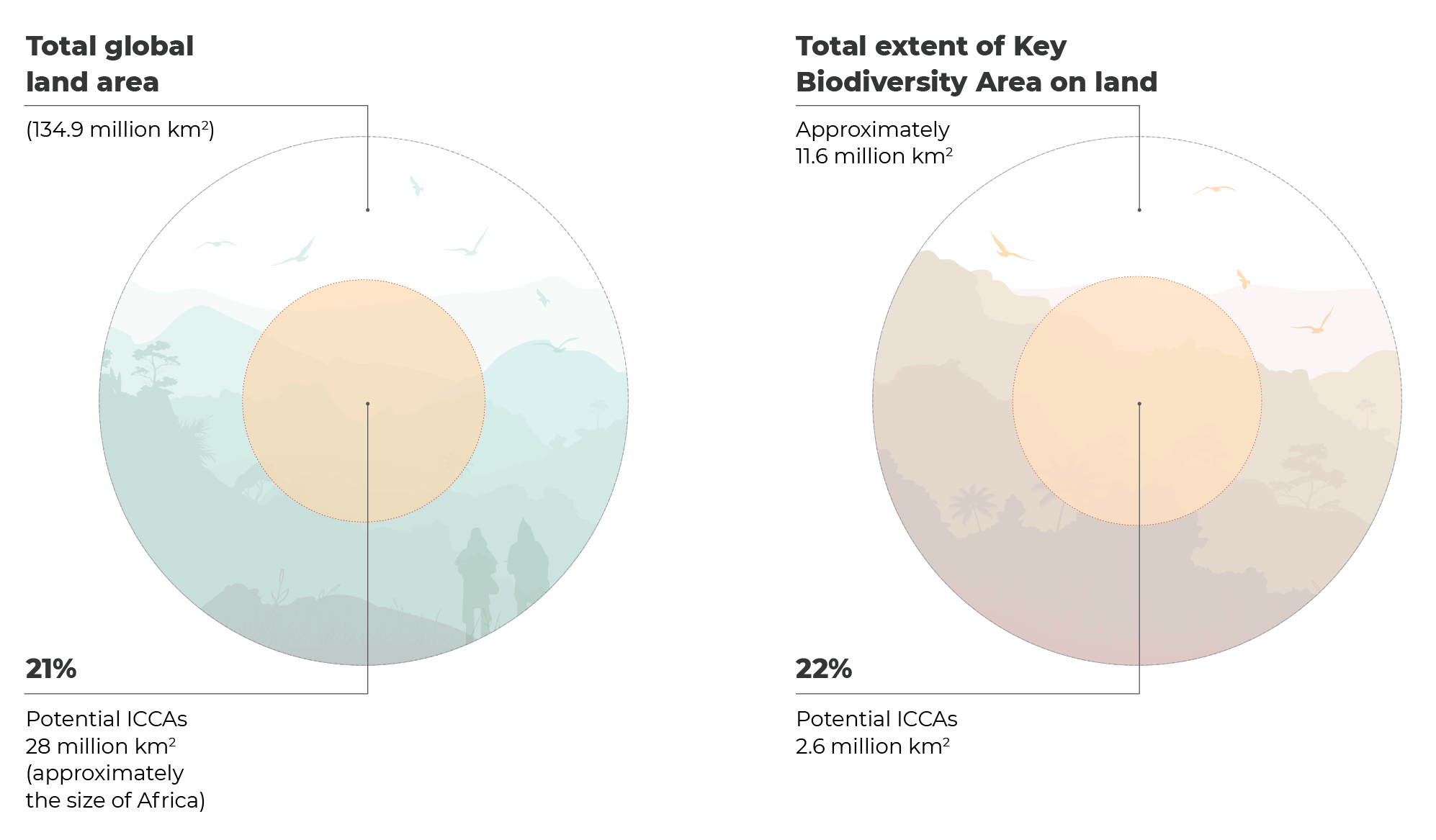

It is estimated that potential ICCAs cover more than one-fifth (21%) of the world’s land (approximately the size of Africa) and over one-fifth (22%) of the extent of the world’s terrestrial Key Biodiversity Areas. As custodians of such a large proportion of the world, they must be acknowledged and respected as rights-holders, protagonists, and leaders in relevant decision-making processes, and their rights to self-determination and collective lands and territories must be recognized and upheld so they can protect themselves from threats.

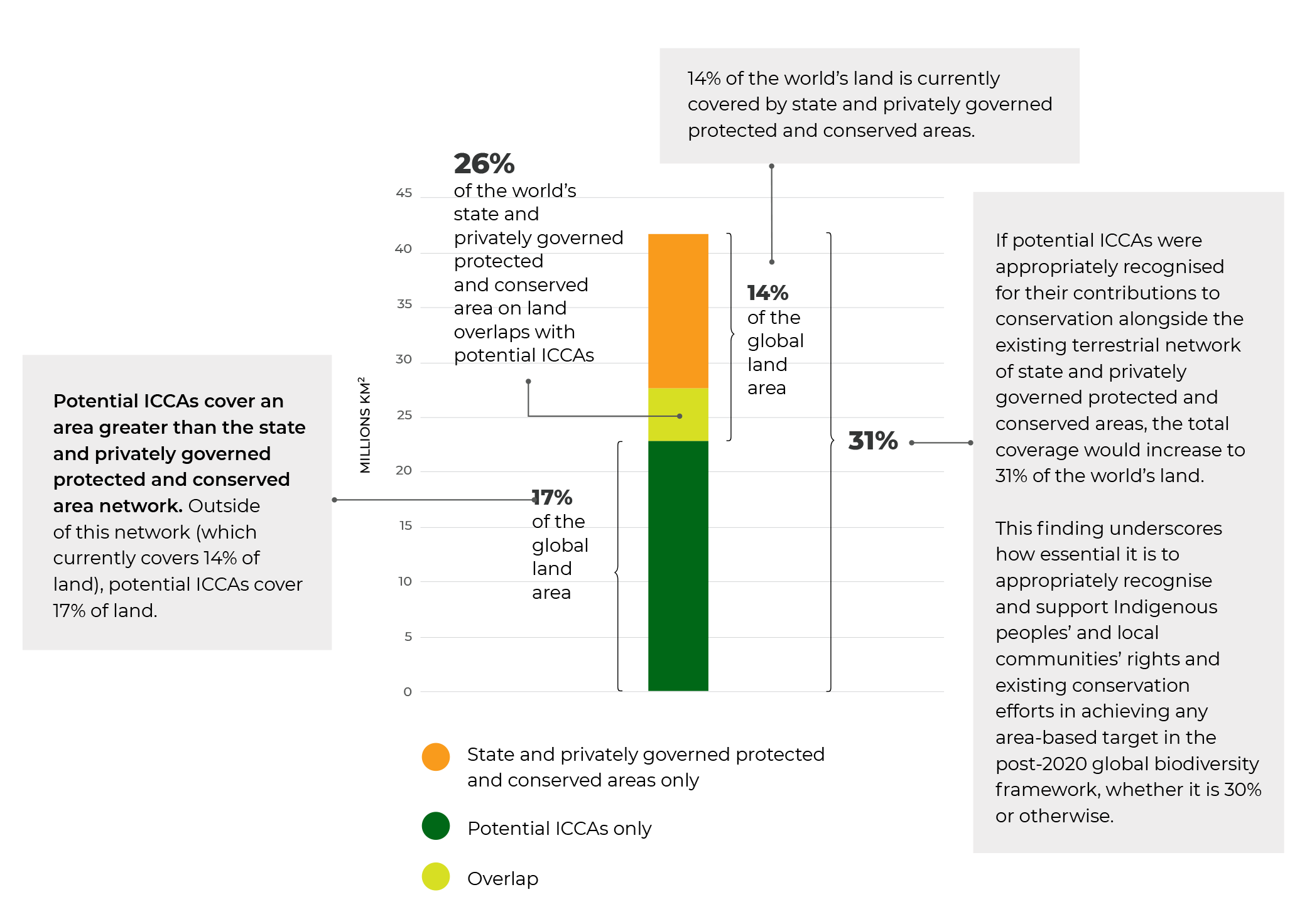

At least one-quarter (26%) of the world’s state and privately governed protected and conserved area on land overlaps with potential ICCAs.

Therefore, Indigenous Peoples and local communities are likely the de facto custodians of many existing protected and conserved areas without being formally recognized as such. In many cases, it is precisely because of Indigenous Peoples’ and local communities’ actions and contributions to biodiversity that these sites have been deemed ‘suitable’ for formal protection. This overlap also raises significant concerns with the historical and continuing human rights implications of protected and conserved areas for Indigenous peoples and local communities, including potential forced displacement, undermining of customary and local governance and management systems, and criminalization of cultural practices.

Almost one-third (31%) of the world’s land may already be covered by areas dedicated to conservation and/or maintaining the land in good ecological condition.

If potential ICCAs were recognized for their contributions to conservation alongside the existing state and privately governed protected and conserved area network (14% of the world’s land), the total coverage would increase to 31%. This finding underscores how essential it is to appropriately recognize and support Indigenous Peoples’ and local communities’ rights and existing conservation efforts in achieving any area-based target in the post-2020 global biodiversity framework, whether 30% or otherwise. Indigenous Peoples, local communities, and civil society organizations have expressed serious concerns with the current draft’s Target 2. This analysis illustrates the opportunity and needs to explicitly incorporate human rights, governance diversity, and equity into the target and ensure its implementation respects Indigenous peoples and local communities as rights-holders.

Potential ICCAs cover an area greater than the terrestrial state and a privately governed, protected, and conserved area network.

Outside of this network (which currently covers 14% of land), potential ICCAs cover 17% of the land. In many cases, Indigenous Peoples and local communities govern and manage their territories and lands in ways consistent with the definition of a protected or conserved area. However, it is up to the custodians as to whether and in what ways they choose to engage with the ‘official’ protected and conserved areas system and related designations and forms of identification and reporting.

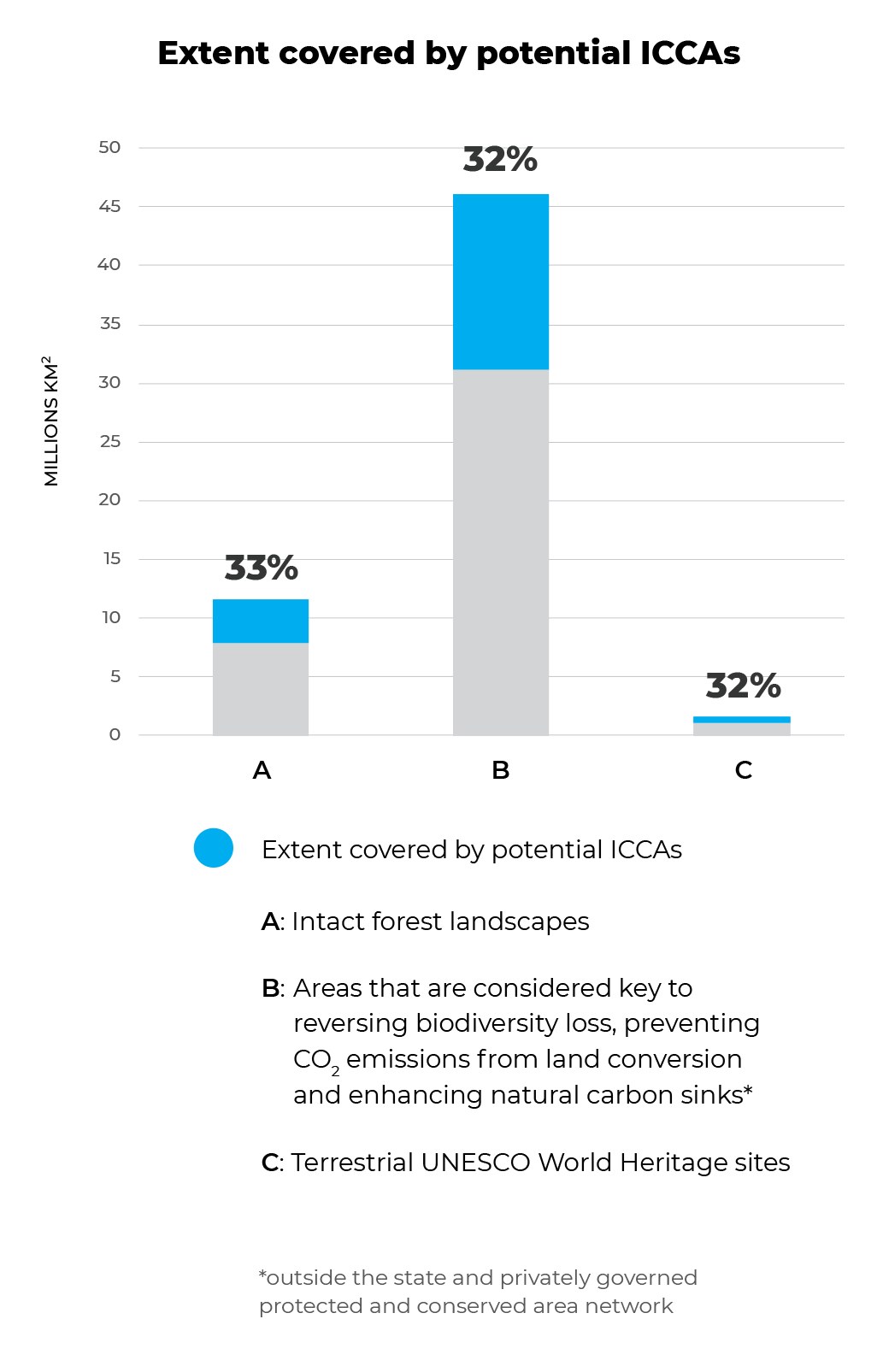

Potential ICCAs cover at least one-third (33%) of intact forest landscapes globally.

They also cover at least one-third (32%) of areas considered key to reversing biodiversity loss, preventing CO2 emissions from land conversion, and enhancing natural carbon sinks. This finding indicates that in addition to being rights-holders to these territories and areas, Indigenous Peoples and local communities are also the protagonists and agents of change in local-to-global efforts to protect forest landscapes, halt further biodiversity loss, reduce wildfires, and mitigate climate breakdown.

UNESCO recognizes some areas governed by Indigenous peoples and local communities as natural sites of outstanding universal value.

Almost one-third (32%) of the extent of UNESCO’s Natural and Mixed World Heritage sites on land overlaps to some extent with potential ICCAs. This role should be acknowledged and supported, with subsequent conservation efforts aiming to reinforce and support the deep connections between cultural and biological diversity in Indigenous Peoples’ and local communities’ lands and territories and the social, cultural, and spiritual practices that nurture and sustain them.

At least 16% of the extent of potential ICCAs faces high exposure to future development pressure from commodity-based and extractive industries.

Although these high industrial pressures are not inevitable, it is important to be prepared for this possibility, including proactively and urgently supporting Indigenous Peoples and local communities to secure their rights to their collective lands and territories and governance systems. This 16% includes areas under high pressure, but the other 84% of the extent should not be considered free from development pressure. Given the significant linkages between potential ICCAs and areas of crucial importance for biodiversity and a healthy climate, supporting Indigenous Peoples and local communities to secure their rights and protect and defend their territories and areas against industrial pressures should also be a priority for all actors in the conservation sector.

Conclusions and recommendations

The time is now to recognize Indigenous Peoples and local communities as the true agents of transformative change. They are so central to sustaining the diversity of life on Earth that it would be impossible to address the biodiversity and climate crises without them. Supporting Indigenous Peoples and local communities to secure their collective lands and territories of life and a minimum bundle of rights is a key ‘missing link’ in global commitments and national-level implementation. Of particular importance are the rights to self-determination, governance systems, cultures and ways of life, and rights to access information, access justice, and participate in relevant decision-making processes.

In practical terms, pursuing this agenda requires a massive increase in social, political, legal, institutional, and financial support for Indigenous Peoples and local communities, primarily from nation-state governments and public and private financial institutions. It is time for social movements and civil society organizations working on human rights, conservation, climate justice, and land issues to come together in this collective effort. Lawyers, legal advocates, researchers, journalists, communicators, and others with specialized skill sets also have critical roles.

The overall recommendations of Territories of Life: 2021 Report are to:

1

Recognize and respect the central role of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in sustaining a healthy planet and the deep cultural and spiritual relationships and governance systems through which they do so.

2

Support Indigenous Peoples and local communities to secure their collective lands and territories, strengthen their self-determined governance systems, and sustain their cultures and ways of life on their terms. This requires significant reforms in national political and legal systems and international financial and economic systems.

3

Embed and uphold human rights (including Indigenous Peoples’ rights and other group-specific rights, where relevant) in all policies, laws, institutions, programs, and decision-making processes that affect Indigenous Peoples and local communities, both internationally and domestically.

4

Halt the drivers of biodiversity loss and climate breakdown, and halt threats and violence against the people and communities defending our planet.

5

Develop human rights-based financing as a key lever for equitable and effective implementation of global commitments, including biodiversity, climate, and sustainable development.