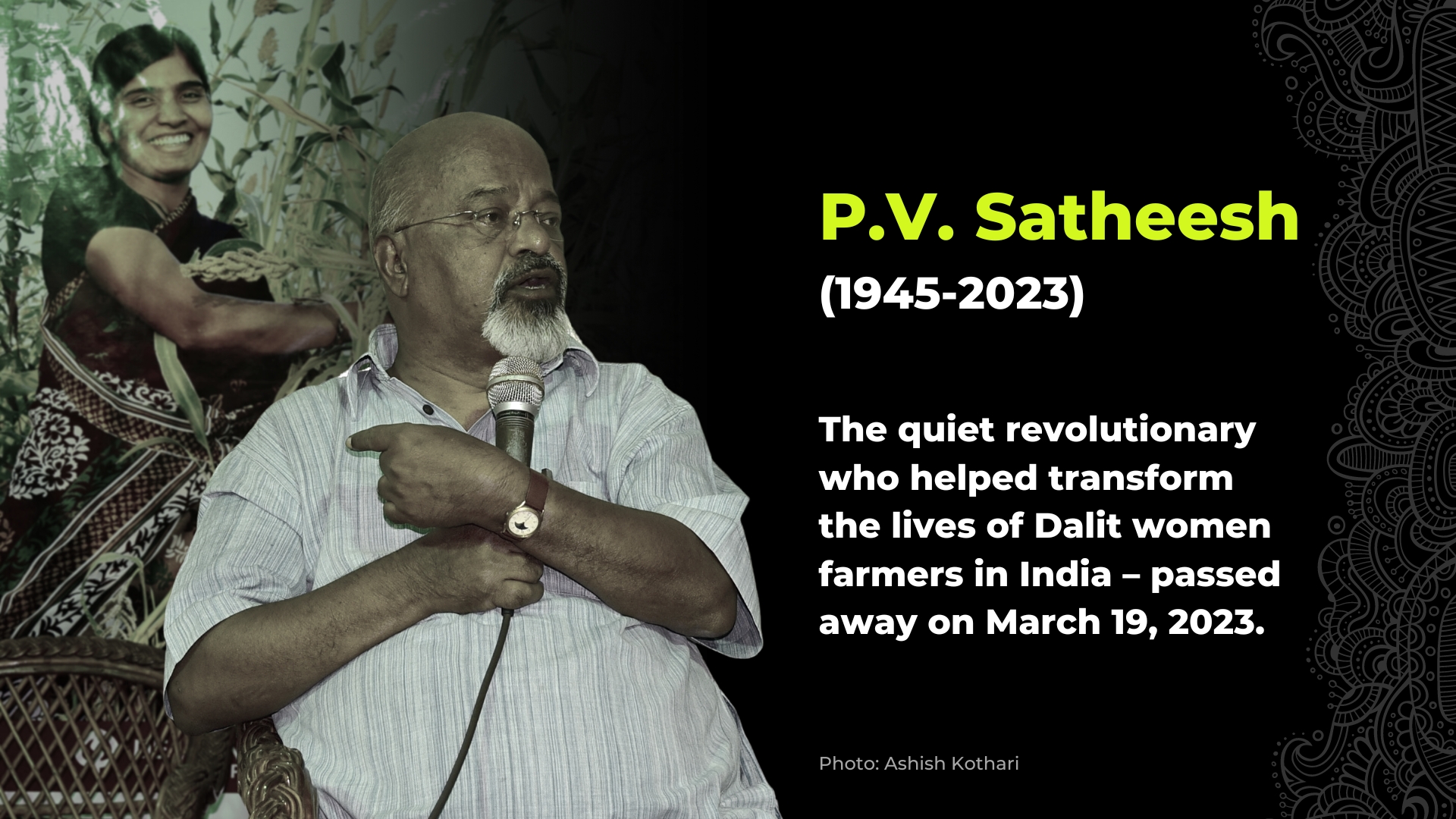

P.V. Satheesh—the quiet revolutionary who helped transform the lives of Dalit women farmers in India—passed away on March 19, 2023. He was 77. The founder of the Deccan Development Society worked for agro-biodiversity, food sovereignty, women’s empowerment, Dalit rights, social justice, and local knowledge systems

First published on 04/18/2023, and last updated on 04/20/2023

Written by Ashish Kothari, Member of the Council of Elders, ICCA Consortium

Ashish is with Kalpavriksh (ICCA Consortium Member) and Vikalp Sangam, Pune, India

Two kinds of people make revolutions, some loud and in-your-face, some unobtrusive, behind-the-scenes. A remarkable example of the latter passed away on 19th March, mourned by several thousand people whose lives he directly touched and many more who were indirectly inspired by his work.

Periyapatna Venkatasubbaiah (PV) Satheesh, communicator, innovator, activist, and much else, was one of the founders of the Deccan Development Society (DDS, ICCA Consortium Member). I have worked for over four decades on environmental, development, and livelihood issues in India, and I can confidently say that DDS has been the most inspiring example of how those marginalized and oppressed by the dominant society can express their agency and power.

Having started with a few dozen women farmers, DDS has grown to over five thousand women and their families, the vast majority belonging to Dalits and some Adivasi or pastoral communities. Men in many of these households are also playing important roles. Still, women are at the forefront of what has been a series of extraordinary revolutions in agriculture, media, and gender relations. And Satheesh has been at the heart of this transformation. Born in 1945 in Mysore, Satheesh studied at the Indian Institute of Mass Communication, New Delhi, and took up journalism. For almost two decades, he was a television producer for India’s official TV channel Doordarshan, making programs related to rural development and literacy in what was then the United Andhra Pradesh (more recently divided into Telangana and Andhra Pradesh). He was essential in the innovative Satellite Instructional Television Experiment (SITE) in the 1970s. Growing tired of the inevitable constraints of official positions and journalism that treated people as items for consumption, he quit. In the early 1980s, he and some others moved to the rural parts of Medak district, establishing the Deccan Development Society (DDS) and hoping to help with ‘poverty alleviation.’ Soon after, though, he realized that poverty was less about money and more about lack of basics like food; and that on these issues, there was much he could learn from the local ‘illiterate’ farmers, especially the women. This led him and others to seek a community-led pathway of agricultural transformation that became the foundation of some genuinely revolutionary decades. DDS was soon converted into an organization with a central governance role of Dalit women farmers.

Much has been written and spoken on DDS’s many achievements – amongst the first to fight for and obtain land rights for women, the initiation of women-led village-level sanghas federating over 75 villages, the first to start a mobile biodiversity festival (an annual event for over 20 years now), the first to set up a community radio station (well before it became ‘legal’ to do so in India), the achievement of not only food security for 5000 families but also food sovereignty, the first (and perhaps still only) official Krishi Vigyana Kendra (Agricultural Science Centre) that is jointly run by government-appointed scientists and Dalit farmers, the first (and again, possibly only) parallel Public Distribution System run by these farmers which procures local grains (millets) and supplies at affordable rates to local poor families, a co-initiator of a farmer-led organic certification system called Participatory Guarantee Scheme (PGS, which is recognized by the government), a producer-consumer link called ConFarm linking over 100 families in Hyderabad with the Dalit farmer families, perhaps India’s first millet restaurant in the town of Zaheerabad and the sangam markets (which he called ‘the market of the dropouts’) to connect rural producers to rural consumers, the initiation of national and global networks to promote millets including the Millet Network of India (MINI) and Millet Sisters.

I will not here go into details on these; they can be found elsewhere, including on the DDS website. Here I focus on Satheesh after one final comment on DDS.

For me, the most remarkable transformation achieved by this group has been that of India’s most oppressed section, Dalit women. The way they have broken through dominant caste and gender stereotypes and hierarchies and journeyed from being landless laborers subject to the mercy of dominant caste landlord men to sovereign producers who can hold their heads high while facing any audience is nothing short of revolutionary. An achievement Gandhi would likely have labeled a true representation of Swaraj.

Back to Satheesh. People who worked around him recalled how he seemed to wake up every morning with a new idea. Many of the initiatives above were his brainchild, though he was also quick to acknowledge that without what he got from the Dalit farmers, he may have never thought of them. He would scold anyone who called these women ‘illiterate,’ stressing that they were ‘non-literate’ and as intelligent as any ‘literate’ person (and possibly wiser). Vinod Pavarala, Professor and UNESCO Chair on Community Media at the University of Hyderabad, recalls how when he first approached Satheesh to lecture to his students, Satheesh told him to bring students to the villages to learn from the Dalit women. Salome Yesudas, who worked as a scientist at the Krishi Vigyana Kendra in Pastapur, recalls Satheesh’s insistence on having Dalit women farmers on the Kendra’s Scientific Advisory Committee and steering its scientific work towards complementing the women’s traditional knowledge rather than displacing it as other KVKs across India were doing. Thousands of visitors to DDS have been stunned and inspired listening to not only the agricultural knowledge of women farmers but also their skills at making movies and running a radio station, both part of what is possibly India’s first Dalit-led media unit, the Community Media Trust. This was an outcome of Satheesh’s firm belief that non-literate women marginalized by the dominant society can do anything with some facilitation. I recall the first time I went to DDS and was unnerved by the fact that instead of me being behind a camera taking pictures of others, I was often in front of one wielded with expertise by a DDS woman.

The memories that the five-thousands members of DDS have of Satheesh could fill several volumes. Here is what General Narsamma, who along with Algole Narsamma has been running the community radio, said at a memorial function for Satheesh: “I met him as a child; he was a playmate, teacher, and guide, and above all a friend for life. We used to fly kites, play colors, and share food; he used to cook mutton and delicious foods and take us to local festivals. He helped us join Pachha Saale (the DDS-established alternative school), which children and Satheesh set up to suit our needs.”

I first got to know Satheesh well around the turn of the millennium when Kalpavriksh took on the coordination of India’s National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP) process. I invited Satheesh to join the Technical and Policy Core Group entrusted with handling the process, involving widespread participation across the country. We had then decided to facilitate biodiversity action plans at local levels (as also state, bioregional, thematic, and national levels), and Satheesh committed to making one for the area DDS operated in.

With hundreds of local farmers and others involved, DDS produced the first of about 100 action plans under NBSAP. Its process involved a mobile biodiversity festival, which I was fortunate to participate in. Satheesh also gifted us all with t-shirts made for the occasion, depicting a diversity of seeds; over 20 years later, I still wear the two I got. Since that first visit, Kalpavriksh and DDS have collaborated on many activities, including initiating Vikalp Sangam (Alternatives Confluence), a national platform to bring together radical alternatives.

As Michel Pimbert, professor at Coventry University (UK) and long-time associate of Satheesh, recently said in an online memorial, Satheesh was a revolutionary in the Gandhian sense. His was a quintessential satyagraha approach, speaking truth to power while trying to persuade it to change. He was confident in working with government agencies in advocating policy and programmatic support for DDS-like work, inviting them to all functions and events, and trying to win them over to a grassroots-first approach.

But he would also not hesitate to use firm words when necessary, telling them what he thought of perverse or regressive policies or protesting the politics and corporate profit-making behind Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs) or the Green Revolution.

In the same vein, recalls Rukmini Rao, who worked with DDS for many years and is on its governing board; while Satheesh firmly advocated the centrality of women in agriculture and media, he also persuaded and enabled men to transform into champions of small-holder sustainable agroecology. I recall one visit to DDS in 2015 when Satheesh asked us to visit male sugarcane and flower farmers who had shifted to organic, biodiverse methods.

Agriculture and media were not the only domains Satheesh innovated in. His interests, ideas, and actions spanned ecological, sociocultural, political, and economic spheres. As Kavitha Kuruganti of the Association for Sustainable and Holistic Agriculture (ASHA) recounts in her obituary: “Agro-biodiversity, food sovereignty, women’s empowerment, Dalit rights, social justice, local knowledge systems, participatory development, community media, alternative education and the power of collectivization were all part of the impressive work he led for over four decades.”

Satheesh’s many contributions will last well into the future. One that has taken firm footing not only in the Medak district but in India as a whole and globally is the recognition of millets as wonder foods that are as relevant to today and tomorrow as they were to yesterday. He called them the ‘crops of truth’ and showed how they are the solution to food and livelihood insecurity affecting India’s poorest and most marginalized people. His role in millets being included in India’s Food Security Act has been acknowledged by civil society organizations instrumental in its framing.

As Appiko Movement activist Pandurang Hegde has recalled, his advocacy also managed to persuade state governments such as Karnataka and Odisha to include millets in various government programs, including the Public Distribution System. Several organizations have acknowledged his role in encouraging agroecology in areas far from India, including Canada and many parts of Africa.

Undoubtedly, his work was one of the foundations of India’s advocacy for 2023 to be declared the International Year of Millets by the United Nations General Assembly in 2021; just two years before this, DDS deservedly got the UN Equator Prize for exemplary work on biodiversity-based livelihoods.

Ironically, Satheesh was to leave us in the International Year of Millets. But, likely, he would also have been unhappy with how governments and private corporations are hijacking the millet agenda. Instead of a priority focus on small-holder-based domestic food sovereignty, the Indian government’s millet push is putting exports and elite consumption center-stage.

Were he around, Satheesh is likely to have had many scathing things to say about this, perched on his favorite spot outside his humble house, under a set of lovely trees. It was usually at this throne of his that I met him whenever I visited Pastapur. From here, he brought forth his many brilliant ideas and spoke in his down-to-earth manner to all kinds of visitors. It was a pilgrimage to this spot, and I will make it a point to visit it on my next trip to DDS. I will not be able to hug him physically, but I am sure I will still be able to connect with his spirit and hear his chuckle as he makes a joke about himself or some crazy government initiative. Like thousands of others, I will miss him, but I am consoled by the fact that he will continue to inspire and guide me.

[Editor’s note: The Hindu has previously published a version of this article in their Frontline magazine]