First published on 03/17/2020, and last updated on 09/17/2020

By Lucas Quintupuray, Member of the ICCA Consortium Council with special responsibility for the Southern Cone of South America.

Mapuche ta iñchiñ feyta Wallmapu mülepalu

We are Mapuche and we inhabit Wallmapu.

Our Mapuche Nation-People live in the lands that are in the south of Latin America. The latitudes of our ancestral territory, Wallmapu, are delimited by the seas, pu fütxa lafken, today called the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Like other Peoples who pre-exist the modern Nation States, we have our own ancient identity, inseparable from our cosmovision, language and ancestral organization. Our ancestors knew how to live and cross these territories of life of which we are part, of which we are but one more energy. Like them, we continue to maintain that our territory, Wallmapu, does not recognize the imposed borders that seek to convince the population that the Andes is a limit or border, when we know that it is a road or rüpü. With the arrival of the Spanish and the persecutions during the establishment of the States of Chile and Argentina, these forests, mountains and landscapes, have been a place of refuge for the communities who resisted the conquest with dignity, retaining sovereignty of the territory until the end of the 19th century.

Genocide and stories of resistance

Sovereignty over the territory came about during the so-called “Conquest of the Desert” in the sector that is now named Argentina, and, the “Pacification of Araucanía” in the part of the territory that is today known as Chile. These two campaigns, or critical events, that disrupted our lives and communities we call genocide; in that they were premeditated, intentional, separated families from their children, resulted in concentrations of our people imprisoned in different parts of Patagonia and Buenos Aires and led to the death of many of our ancestors. Thus began the loss of territory and language, ways of life and social and political organization. Our grandmothers and grandfathers did not let us forget these times, but at the same time, to save the coming generations from persecution and oppression, they denied us part of our knowledge, our people concealed their identity, as a conscious decision and a form of self-defense.

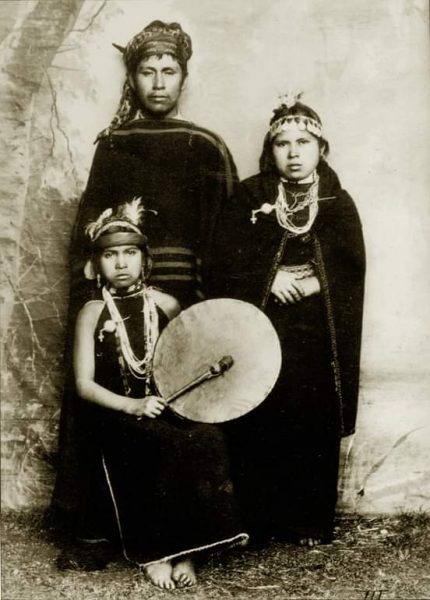

Woman playing the kultxüg © Taiñ Füchakecheyem

In the stories of those difficult times, our elders recounted how they knew how to survive wartime in spite of the difficulties they faced. And that is how we also knew how to recognize the traces of our history and culture that our elders left us: words in our language, customs or ways of life, traditional foods that were shared, how to live tüfachi mapu mew (in this land). Some of us have even kept the names of our families, today surnames, all these signs that still remain in the territory, showed us the way. They were given to us as small breadcrumbs that over time became questions, the search for answers and the recovery of what had been denied us. Many of the young or new generations were aware of our origin, and finding ourselves orphans of some knowledge, relying only on these crumbs, we put into practice what was transmitted and what we learned along the way despite the difficulties we face in our daily lives, we decided to nourish our püllü or spirit that seeks to return to being Mapuche.

Youth and restoration: pu ayekawe (instruments)

We young people say: “our ancestors manifest themselves in us.” So, we have undertaken an uprising that was replicated at all points of our Wallmapu or ancestral territory. We are learning and replicating what they teach us among peers, recognizing ourselves by raising our wenufoye or Mapuche flag, created by the militancy that preceded us in the 90s, the symbol that has unified and outlined us as a Nation-People. Through it, we make explicit our Mapuche being, we talk about our cultural, philosophical and spiritual matters, distinguishing ourselves from the recent National States. We are not Argentinians, nor Chileans: mapuche ta iñchiñ, we are Mapuche, people of the land. Thus, each young Mapuche today rises, learns about his people, transmits and makes what we are visible, from wherever he is, we work in different ways, but without losing the objective that guides us, to continue existing as a People.

Man playing the Txutxuka. © Taiñ Füchakecheyem

Iñche ta Lucas Kintupuray pigey, Logko tañi lof mew. Küpan Lof Correntoso lafken mew, tüfa mew müley tañi ruka ka tañi tuwün tañi kupalme (My name is Lucas Kintupuray, I am the leader of my community at Correntoso Lake, that’s where my house is, my origin, where I’m descended from). As a young man I work in my Lof restoring ancient instruments.

These are of great need for many Mapuches who, with or without their own land, rise up throughout Wallmapu (ancestral territory), for those who feel the need to use them in one way or another, to nourish the spiritual. However, it is also a political and philosophical-cultural act since, each time they are played, we declare that we are still alive, that our futakeche yem (ancestors) live on in us. This role led me to inquire about the construction of these instruments, which I found very difficult to learn since, as a consequence of genocide and persecution, our people are very cautious in transmitting this küzaw or activity. We can say this is a sequel of the events.

However, I continue to try really hard to improve my work, recognizing great progress and being oriented to satisfy my brothers and sisters who contact me from many places. These instruments accompany them when they go to do ceremonies, on the new paths that their journey as Mapuche takes them in the context that we are currently living, on their return or recovery of the territory and/or of their language, affirming their identity. And this is why I will share with you some of our instruments, our ancient art, our history.

The construction of these instruments has allowed me to meet countless people from our Nation-People. In these meetings that take place in different parts of the country I usually hear phrases like: “I have been looking for one for a long time “, “I wished that this moment would come“, “my heart knew I was going to get one” or “we needed one to strengthen ourselves“. These words demonstrate how deeply the instruments are needed. By having them, it proves that it is not a utopia to want to connect to the root, as they seek knowledge and begin this recovery process through the instruments, since they know that it is the way to show nature that they are still alive, still standing and aware of their origins.

Various Mapuche instruments. © Maru Cofre Logkopag

When we play the instruments in ceremonies or celebrations, we demonstrate to the different energies that we know our origin and understand our role: we are defenders of life, of the territories, we are one more energy, we are part of the whole. To recuperate what was taken from us and the growth that our Nation-People is enjoying, guarantee that the territories of life are going to be able to sustain themselves and their ancient defenders.

As long as there are cohiue, more cohiue will grow.

The cohiue is an ancient tree of great height and abundant in many territories, due to its easy growth and its quantity of seeds. We say: “if a cohiue falls, 10 more cohiues will grow. If a Mapuche dies, ten more will rise. While there are Mapuches, more Mapuches will be born”.

In this song by Anahi Rayen Mariluan, presented with her permission, you can hear various ancestral Mapuche instruments.

Mapuche instruments

- Kultxüg: Fundamental element of the Mapuche Nation People. Its symbology represents the 4 elements that make up all life, meli witxal mapu, (the four points of our ancestral territory), our cosmovision and how we see life. This percussion instrument is made from txiwe or foye wood, essential medicinal trees for our people. The rali or bowl is handcrafted, its skin made from goat or foal hide, tightened with leather strips or horse hair and played with a colihue stick. This ancient instrument is present in all our ceremonies and celebrations and is considered the most important in Mapuche life.

- Ñorkin: Wind instrument. It is made with colihue cane, which is folded and hollowed, sealed with animal guts, then wrapped in wool or leather. At one ends it has a cow horn that serves as an acoustic chamber, its various sounds and melodies are generated by the person who plays it who seeks to blend with the tones of the kultxüg.

- Pifillka: This small wind instrument is made from various native woods. It is given an elongated shape by making a hole in one of its ends. To use it, it is first tuned with water or muday (a drink made from corn, wheat or gülliw – pine nuts) and is blown vigorously generating constant and repetitive sounds.

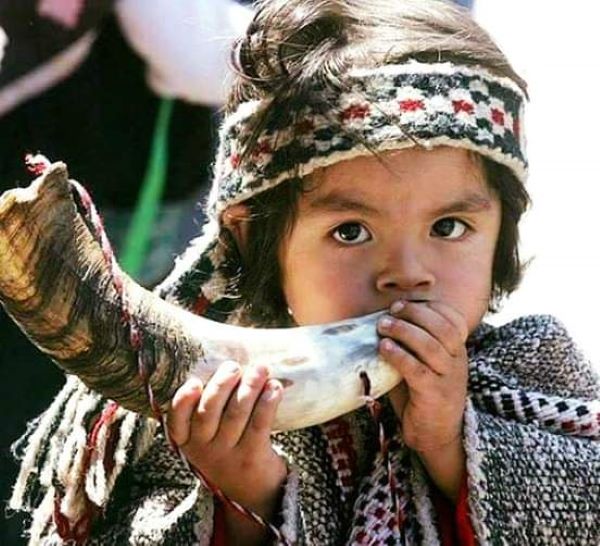

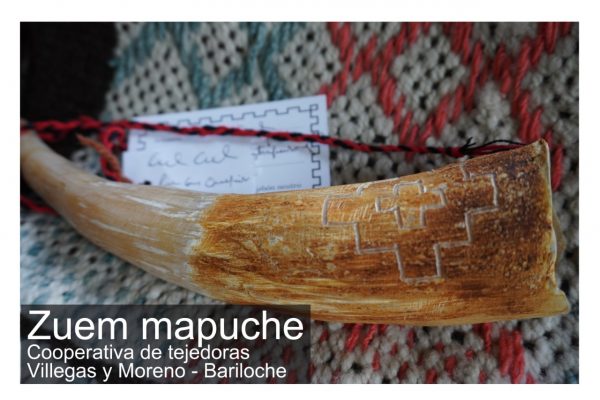

- Kull-kull: This instrument was used by our Nation People in wartime to sound an alarm. Very high-pitched sounds were generated which produce an echo, in this way, their sound can reach great distances in flat places or areas. It is made with a cow horn with a hole in one of its sides so you can blow it, the werken or messengers are those who carry this ancient instrument.

- Txutxuka: This instrument can measure between 4 and 6 meters in length. It is made with a thick colihue cane that is split lengthwise, hollowed out and then joined. Finally, it is sealed with animal guts, as is done with the ñorkin, and it is wrapped with wool or leather to give it firmness. A large cow horn is placed in its thickest part that serves as an acoustic chamber. It’s not at all easy to learn the technique to play it, so the txutxuqueros or txutxukafe (the people who play it) are very important. These people generate melodies for different moments producing soft and relaxing melodies.

Man playing the Txutxuka. © Taiñ Füchakecheyem

Featured image: Child playing the kull-kull. © Taiñ Füchakecheyem.

Pictures of instruments: © Taiñ Füchakecheyem, Manu Cofre Logkopag and Lucas Quintupuray.