For the first time in the UN Convention on Biological Diversity, the new global biodiversity framework adopted in December 2022 recognises and commits to protecting environmental human rights defenders. During COP15, a side event co-organised by the International Land Coalition, Natural Justice, and the ICCA Consortium delved into what this means in practice and what women face on a daily basis as they defend their territories of life in diverse contexts

First published on 04/23/2023, and last updated on 04/25/2023

By Holly Jonas (Global Coordinator of the ICCA Consortium Secretariat)

As external threats to nature continue to grow, so too do threats to the people, communities and organisations who defend our planet. Every year, hundreds of people are killed and countless more are threatened, harassed, and injured for defending their communities, territories, and ecosystems against these threats. Among the most targeted are Indigenous Peoples and local communities who defend their collective lands, waters, and territories of life against destructive and extractive industries such as logging, mining, industrial livestock and agriculture, physical infrastructure and energy projects, and aquaculture and fisheries. In addition to these direct drivers of the biodiversity and climate crises, they also face such threats from defending themselves and their territories of life against top-down and exclusionary forms of conservation, armed conflict, and the effects of broader economic and political trends such as neoliberalism and authoritarianism.

In December 2022 in Montreal, the main focus of the 15th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD COP15) was the final stage of negotiations of the post-2020 global biodiversity framework. Throughout the multi-year negotiation of the post-2020 framework, one of the ICCA Consortium’s main priorities was to advocate for explicit recognition and protection of the rights of environmental and human rights defenders, and particularly Indigenous Peoples and local communities who are defending their territories of life. As part of this advocacy strategy, the ICCA Consortium supported members of Indigenous Peoples and local communities to share their experiences, perspectives, and recommendations on these issues before and during COP15. The particular emphasis of the side event was to highlight the additional, and often under-reported, intimidation women land rights defenders face, from within and outside their own communities.

The following is a summary of a COP15 side event called “Protecting biodiversity: the crucial role of women land and environmental defenders”. Co-organised by the International Land Coalition, Natural Justice, and ICCA Consortium, the event was held on 8 December 2022 from 18:00-20:00 ET in the CEPA Pavilion. Moderated by Gino Cocchiaro (Natural Justice, member of the ICCA Consortium and ILC), speakers included:

- Michel Forst, former UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Defenders and current Special Rapporteur on Environmental Defenders for the Aarhus Convention;

- Esther Wah, All Burma Indigenous Peoples Alliance and ICCA Consortium Honorary member;

- Milka Chepkorir, Sengwer (Kenya) and the ICCA Consortium’s (then) coordinator for defending territories of life;

- Eva Hershaw, International Land Coalition and the Data Working Group of the Alliance for Land, Indigenous and Environmental Defenders (ALLIED); and

- Yves Lador, Earthjustice.

Michel Forst (former UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Defenders, current Special Rapporteur on Environmental Defenders for the Aarhus Convention and ICCA Consortium Honorary member) opened the event with the following remarks:

“The rights of human rights and environmental defenders must appear in the main text, not just in the preamble. Access to justice is a key element of my mandate as SR on Environmental Defenders. I hope the final text will also guarantee access to justice. Social justice and environmental justice go hand-in-hand. We can’t save biodiversity without defending those who are defending it.”

Michel Forst underscores the importance of explicit recognition of human rights and environmental defenders in the post-2020 global biodiversity framework.

In the documentary “The Illusion of Abundance”, filmmakers Erika Gonzales Remirez and Matthieu Lietaert follow the stories of three women defenders in Peru, Brazil and Honduras, fighting at the great personal risk against the never ending thirst for cheap resources and raw materials.

A clip from the documentary “The Illusion of Abundance” was screened during the COP15 side event.

Esther Wah (name changed for security reasons) is an Indigenous woman with the All Burma Indigenous Peoples Alliance. Since the military coup in February 2021, over 60,000 people, including 3,000 women, have been arrested and over 2,000 people, including 300 women, have been killed. An unknown number of environmental defenders have been arrested and killed. Within their network alone, over 30 people have been arrested. As Esther shared:

“We couldn’t organise communities anymore. I felt lost and everyone was scared to raise their voices. We could be arrested at any time. I changed my name and tried to find ways to raise our communities’ voices. I could not stay in the country anymore, so I moved to [a neighbouring country] several months after the military coup. Even there, we didn’t feel totally safe. If we raise our voice in social media or show our face or use our real name – even if we are not in the country, they can still arrest our family members. There are lots of mental problems from living with fear.”

Before the military coup, people could still walk and protest. But after the coup, there was no rule of law and no respect for human rights. Families were torn apart, women and children became more vulnerable, and environmental defenders were forced into hiding. As Esther implored, “How can we defend our forests and natural resources? How can we contribute to climate change mitigation? The coup is impacting the whole world. The military junta is the biggest perpetrator of climate change and climate change doesn’t have boundaries.” The rights of Indigenous Peoples are not only a human rights issue, but they are also an environmental issue.

She called on donors to support environmental defenders directly, not only through organisations, and to support access to information in local languages, including about how they can get support. She urged international organisations to not cooperate or work with the military junta to avoid giving it legitimacy. Finally, she asked everyone to stand in solidarity with the Indigenous Peoples of Myanmar in their fight to protect their forests.

Milka Chepkorir is an Indigenous Sengwer woman and (at the time of the event) coordinates the ICCA Consortium’s stream of work on defending territories of life. Within Milka’s community, women are the agents of passing on knowledge such as the names of trees, and women have agency in defending their territories. However, gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment and abuse are also prevalent within communities, which in turn has implications for how women can contribute to defending their territories of life. For example, some women defenders have been excluded from the community leadership and actions simply because they have married outside the community. Indigenous women face many layers and levels of discrimination and sexism around leadership, identity, marital status, land ownership, and more.

Particularly for women, sharing stories creates a space where they can talk about their challenges. Milka was recently speaking with women leaders from a community in Uganda, whose territory is now part of an exclusionary protected area – “protected from them”. The women shared that they are raped by the Ugandan Wildlife Service authorities when they collect their medicine from the forest. They don’t say that to anyone else though, because they would be discriminated against and their marriages would end. Sharing experiences like this gives confidence to others to share either confidentially or publicly about things that are considered shameful or may have consequences for the same women who have suffered these violations. Data collection and verification processes need to include such information without placing the women more at risk, otherwise the data will miss out on such attacks that women face.

Most organisations that support defenders have been structured around supporting individuals, and some even hand their data to governments, which makes it easy to attack defenders. Milka underscored that we need to bring an end to the individualisation of defenders as it increases their risks of being attacked. We need to see Indigenous Peoples as a collective defending group and as such work towards collective defense of communities and of their lands and territories.

READ MORE: The time is now to #BreaktheBias against women protecting territories of life

Eva Hershaw is Data and Land Monitoring Lead with the International Land Coalition, which has a clear commitment to protecting land and environmental defenders, and she is part of ALLIED’s Data Working Group. Within this group, all the organisations are documenting attacks against defenders. They have a common goal of working collaboratively to align data and paint a broader picture of the violence that defenders are facing, and to say and have more impact together. Global Witness is perhaps the most visible data collector and there are many local data collectors using informal methods and confirming details verbally. They had to respect the different methods and approaches, build data integration structures, and align criteria by which attacks were collective, classified and validated before they could work together on numbers. They put data sovereignty and gender justice at the forefront. They have seen that Indigenous-led initiatives can really bring a lot of value to this work and want to centre data from these groups and from the most local data collectors and build systems to ensure they are not only involved but really guiding this work.

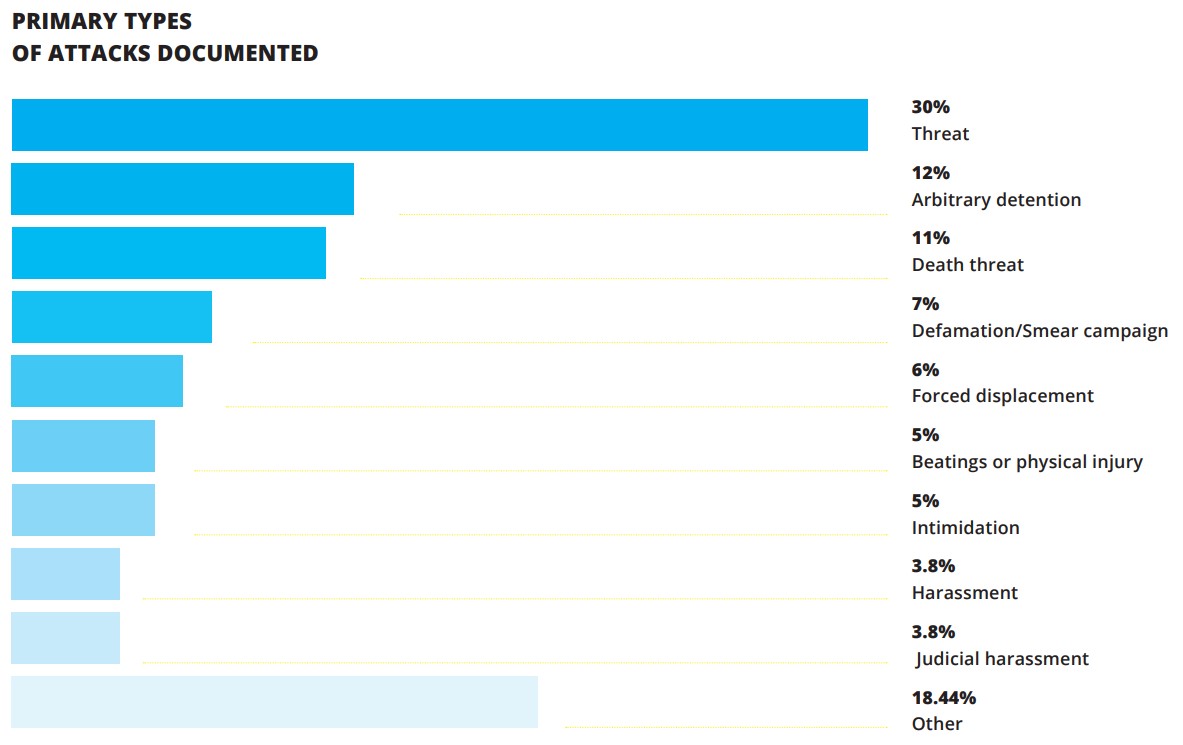

Most reporting is on lethal attacks; it is much more difficult to track non-lethal attacks, even though in 75% of reported killings, they were attacked before then. The Data Working Group just released their first pilot to understand how to fill the gaps of data on non-lethal attacks.

The UN Sustainable Development Goals include an indicator and methodology for governments to track violence against human rights defenders. Within that, land and environmental defenders represent about 50% of attacks. In 2021, ALLIED published a baseline study called “A Crucial Gap: Are governments reporting on defenders?” Of the 162 countries that submitted Voluntary National Reviews since 2015, only three (fewer than 2%) indicated that at least one human rights defender had been killed or attacked. If they’re not measuring it, they’re not going to act on it. In many countries, civil society is filling that gap and defenders are documenting attacks, often putting themselves at risk. There is a role for civil society within this, but it cannot be only them doing this work with no action from governments.

A 2022 brief called “Uncovering the Hidden Iceberg” integrated data from five of the most dangerous countries for defenders. We could see the prominence of certain threats by working with local data collectors and gained a much broader picture of the routineness of attacks. Twenty-nine percent of reported attacks are against women, but it is likely much higher than that because of low reporting and risk of further retaliation. After reporting an attack, defenders continue to live in the public, so there are reasons why they tend to not be reported.

ILC has been following the language around environmental human rights defenders in the draft post-2020 framework and the monitoring framework. They are pleased to see the language retained up to then and underscored the importance of having inclusive monitoring processes with data from Indigenous-led groups, civil society and official sources, and multi-stakeholder validation processes.

Yves Lador (Earthjustice) gathers cases to understand how people standing up for their rights are becoming more exposed. They have found that the most severe and increasingly severe cases are related to environmental issues. In his capacity as UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Defenders, Michel Forst has done many reports on these issues, which helped to identify and raise awareness around the trends. Over time, these stories do have an effect. More and more in meetings like this [COP15], environmental defenders have the possibility to meet and talk together and alliances are being built. This has enormous importance for people on the ground and on the frontlines, as feeling isolated is a big danger. There are also more responses from international institutions, but they need to be stronger.

Yves highlighted the clear language in (then) draft Target 21 of the post-2020 global biodiversity framework about ensuring clear protection for environmental defenders, and about the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities, women and girls, and people with disabilities – sometimes referred to as “people in vulnerable situations” in human rights language. Given the depth of issues encapsulated in this draft target, it should have been higher up in the draft framework but at least it is there; more work on indicators will need to be done.

During the Q&A with panelists, Ruth Spencer (Chair of the Board of the Marine Ecosystems Protected Areas Trust in Antigua) shared some of her experiences with defending nature in Antigua, which has ratified the Escazú Agreement:

“The government still invites investment, including in activities that destroy wetlands and mangroves and threaten communities. Anytime there’s danger to people or the environment or lands are being given away by the government, we link it with aspects of survival and make a fuss so the whole population knows. We are not going to give up these things easily. When an investor from India tried to take up 400 hectares of wetlands, we had protests, radio spots, and invited the public to visit the location. We stopped it from going ahead, but if our advocacy wasn’t as strong, we may not have succeeded.

The Escazu Agreement is a tool for the public to amplify your voices. We have a strong civil society population, we meet with labour leaders, churches and more, and we are reaching out to civil society in other Caribbean countries. Governments sign conventions but they don’t really understand the issues, so civil society organisations have to educate them. Even the Prime Minister of Antigua harasses us, calling us terrorists and uneducated, but we are not prepared to give up our lands and our environment for a few measly dollars. All this work is voluntary and community-based; we are different from NGOs with paid staff who focus on these issues. Reporting on attacks should be mandatory and not voluntary, and should have a specific line for Indigenous Peoples and local communities.”

For more information, see:

- 2022 report of ALLIED’s Data Working Group: “Uncovering the Hidden Iceberg”

- ALLIED’s website and resources

- Reports of the UN Special Rapporteur on human rights defenders