Spurred by a groundswell of public concern over environmental issues in the 1960s (particularly in the global North), the landmark 1972 UN Conference on the Human Environment, also known as the Stockholm Conference, laid the foundations for global governance of the environment and sustainable development and established critical links between human rights, poverty alleviation and environmental protection. The term “sustainable development” was coined and defined in the 1987 Brundtland Report (“Our Common Future”). The 1992 UN Conference on Environment and Development – also known as the Rio Summit – was the largest environmental gathering in history and led to the adoption of the three binding ‘Rio Conventions’ (the Framework Convention on Climate Change, the Convention on Biological Diversity and the Convention to Combat Desertification). It also adopted Agenda 21 and the Rio Declaration, which enumerated a range of fundamental principles of international environmental law, including public participation, precaution and polluter-pays. Since the Stockholm and Rio Conferences, hundreds of international environmental agreements have been adopted on issues ranging from nature conservation and sustainable use of freshwater and marine resources to hazardous substances and pollution.

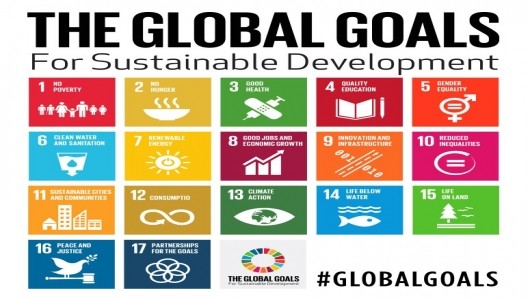

In 2012, the outcome document of the UN Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio+20) recognised Indigenous peoples and local communities in several provisions, including by affirming that “green economy policies in the context of sustainable development and poverty eradication should” enhance their welfare, recognise and support their identity, culture and interests, avoid endangering their cultural heritage and traditional knowledge, and respect non-market approaches to poverty eradication (para 58(j)). In 2015, the UN General Assembly adopted the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which set a global agenda until 2030 to eradicate poverty, protect the planet and ensure that all people enjoy peace and prosperity. Many of the SDGs are relevant to ICCAs, though they arguably pay insufficient attention to the rights and contributions of Indigenous peoples and local communities, including to halting deforestation, conservation of terrestrial and inland ecosystems, and sustainable use of marine and coastal ecosystems.

Within and beyond the global sustainable development regime, strong social movements and civil society networks are pushing for the recognition of collective and individual human rights in the context of different food sovereignty systems, including farmers’ rights, fishworkers’ rights, and livestock keepers’ and pastoralists’ rights. To a degree, farmers’ rights are recognised in the 2001 International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (Article 9) and fishworkers’ rights are recognised in FAO’s 2015 Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-scale Fisheries in the context of Food Security and Poverty Eradication. Indigenous peoples and local communities are also recognised relatively strongly in FAO’s 2012 Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security. The UN Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas (2018) recognises both the individual and collective rights of people and communities pursuing traditional livelihoods such as farming, fishing and livestock rearing.

The ICCA Consortium and its Members have been actively involved in these international processes for several years, as well as civil society campaigns for securing Indigenous peoples’ and communities’ land and resource rights. ICCAs are powerful examples of collective stewardship of lands, waters and food sovereignty systems, rooted in alternative worldviews of livelihoods and wellbeing. Priorities include (among other things): documenting the links between ICCAs and collective rights and responsibilities to common-pool lands, waters and resources; critically analysing mainstream approaches to sustainable development and related financing mechanisms and contributing to alternative narratives of sustainability and wellbeing; strengthening recognition of the rights of subsistence and small-scale farmers, fishworkers, pastoralists and livestock keepers, and hunter-gatherers; and supporting effective implementation of the FAO Voluntary Guidelines on Governance of Tenure and on Small-Scale Fisheries and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Peasants.

Intergovernmental working group on a UN declaration on the rights of peasants

Intergovernmental working group on a UN declaration on the rights of peasants (ongoing negotiations)

FAO Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security

FAO Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security (endorsed in 2012)… Read more “FAO Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security” ▸

FAO Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries in the Context of Food Security and Poverty Eradication

FAO Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries in the Context of Food Security and Poverty Eradication (endorsed in 2015) English | French | … Read more “FAO Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries in the Context of Food Security and Poverty Eradication” ▸

Governing Tenure Rights to Commons: A guide to support the implementation of the Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security

“Governing Tenure Rights to Commons: A guide to support the implementation of the Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries… Read more “Governing Tenure Rights to Commons: A guide to support the implementation of the Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security” ▸

Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

“Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” (adopted in 2015)

Respecting free, prior and informed consent: Practical guidance for governments, companies, NGOs, indigenous peoples and local communities in relation to land acquisition

“Respecting free, prior and informed consent: Practical guidance for governments, companies, NGOs, indigenous peoples and local communities in relation to land acquisition” FAO Governance… Read more “Respecting free, prior and informed consent: Practical guidance for governments, companies, NGOs, indigenous peoples and local communities in relation to land acquisition” ▸

The Future We Want – Outcome document of the Rio+20 Summit

Outcome document of the Rio+20 Summit: “The Future We Want” (adopted in 2012)

UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food

UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food (mandate established in 2008)

UN Special Rapporteur report on the right to food and food sovereignty

UN Special Rapporteur report on the right to food and food sovereignty (2004)

International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture

International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (adopted in 2001) Farmers’ Rights are critical to ensuring the conservation and sustainable use… Read more “International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture” ▸

ICESCR General Comment No. 12 on the right to adequate food

ICESCR General Comment No. 12 on the right to adequate food (adopted in 1999)

Agenda 21

Agenda 21 (adopted in 1992)

The Rio Declaration

The Rio Declaration (adopted in 1992)

The Brundtland Report: “Our Common Future”

The Brundtland Report: “Our Common Future” (1987)

The Stockholm Declaration

The Stockholm Declaration (adopted in 1972)

CALG Reflections and Impressions on the Environmental Defenders Workshop in Philippines

After sharing their experiences in an international workshop on environmental defenders, ICCA Consortium Member Coalition Against Land Grabbing reflects on risk-reduction strategies and the importance of maintaining a united front in the face of threats to territories of life and their defenders. Read more ▸

ANAPAC Lance un Programme d’Identification et de Renforcement des APAC en République Démocratique du Congo

En République Démocratique du Congo, l’ANAPAC, Membre du Consortium APAC, a identifié quatre nouvelles APAC, situées près du Parc National de Lomami. Le réseau poursuit également son travail de plaidoyer auprès des autorités locales, avec beaucoup de succès. Read more ▸

Synergy of Fokonolona Strengthened for the Recognition of their Community Heritage

In Madagascar, as the government develops a legislative framework on special status areas that will include community land rights, TAFO MIHAAVO and MIHARI, both ICCA Consortium Members, are collaborating to ensure that indigenous peoples’ and local communities’ voices are heard, and their areas and heritage secured. Read more ▸

Southeast Asia Explores Sustainable Livelihoods within the Context of ICCAs

Participants from five countries gathered in Philippines for the ICCA Southeast Asia Regional Learning Network’s first event on Sustainable Livelihoods. They shared tools, strategies for local enterprises, and discussed how livelihoods need to be rooted in culture, territory, and strong traditional governance. Read more ▸

La Conservation des APAC par la Transmission des Connaissances : l’Expérience de la Communauté Locale de Kalwaka au Burkina Faso

Cette année, l’Assemblée Générale du Village de Kalwaka s’est concentrée sur la transmission des connaissances sur les bois sacrés du village, exercice qui a permis des échanges particulièrement enrichissants entre aînés, adultes et enfants sur la conservation de ces bois, ainsi que l’émergence de proposition innovantes en lien avec le système éducatif. Read more ▸

3rd National ICCA Conference in the Philippines Calls on Congress to Enact the ICCA Bill

For the third time in the Philippines, more than a hundred stakeholders from indigenous people as well as government agencies and civil society gathered to acknowledge recent gains in the recognition of ICCAs institutionalization and elaborate a plan to continue supporting ICCAs in the country. Read more ▸

Scoping Dialogue on Land Tenure Reform – The Forest dialogue

Prof. José Aylwin – ICCA Consortium Council Member, participated in the conference of the Forests Dialogue to discuss issues surrounding land reform with indigenous peoples, forestry companies, agricultural companies, development agencies and relevant government bodies. Read more ▸

ICCA Consortium members at the UN Oceans Conference (New York, 2017)

Several members and honourary members from the ICCA Consortium participated in this conference whose goal was to be the “game changer that will reverse the decline in the health of our ocean for people, planet and prosperity”. Read more ▸

Open-ended intergovernmental working group on a United Nations declaration on the rights of peasants and other people working in rural areas

From May 12th-19th, 2017, meetings began with the Via Campesina and other organizations or movements of pastoralists, nomads and fishermen. Read more ▸

ICCA Consortium Policy Brief no 6 – Nourishing Life -Territories of Life & Food Sovereignty

The ICCA Consortium is delighted to release its new Policy Brief, which highlights and documents the profound significance of ICCAs—territories of life- and their contributions to the food sovereignty of the peoples and the communities themselves. This is a call for movements that foster food sovereignty and movements strengthening territories of life to exchange knowledge and support each other! Read more ▸

Global Report on the Situation of Lands, Territories and Resources of Indigenous Peoples

This summary of regional reports, written by indigenous researchers and experts, with the guidance of the Indigenous Peoples Major Group Global Coordinating Committee, stresses the importance of securing the collective land rights of indigenous peoples, an imperative to achieving sustainable development for all. Read more ▸

Submission to the African Commission: A Call for Legal Recognition of Sacred Natural Sites and Territories, and their Customary Governance Systems

Report: “Submission to the African Commission: A Call for Legal Recognition of Sacred Natural Sites and Territories, and their Customary Governance Systems” The Gaia… Read more “Submission to the African Commission: A Call for Legal Recognition of Sacred Natural Sites and Territories, and their Customary Governance Systems” ▸

How to Protect Community Lands – Online Resource Guide

Guide: “How to Protect Community Lands – Online Resource Guide” Namati’s Community Land Protection Program and partners use a five-part approach that supports communities… Read more “How to Protect Community Lands – Online Resource Guide” ▸

UN Sustainable Development Goals

UN Sustainable Development Goals (adopted in 2015)

ICCA Consortium Policy Brief no 2

Collective Land Tenure and Community Conservation, Policy Brief of the ICCA Consortium, No. 2, The ICCA Consortium in collaboration with Maliasili Initiatives and Cenesta,… Read more “ICCA Consortium Policy Brief no 2” ▸

ICCA Consortium Policy Brief no 2 – Companion document

Companion document to issue no 2 of the ICCA Consortium Policy Brief Series, Including the full paper and annexes Fernanda Almeida, with Grazia Borrini-Feyerabend,… Read more “ICCA Consortium Policy Brief no 2 – Companion document” ▸

Implementation of the FAO’s International Guidelines on Securing Sustainable Small-scale Fisheries

“Implementation of the FAO’s International Guidelines on Securing Sustainable Small-scale Fisheries” The International Collective in Support of Fishworkers (ICSF) is actively involved in implementing… Read more “Implementation of the FAO’s International Guidelines on Securing Sustainable Small-scale Fisheries” ▸

Securing community land and resource rights in Africa: A guide to legal reform and best practices

Securing community land and resource rights in Africa: A guide to legal reform and best practices FERN, Forest Peoples Programme, ClientEarth and Centre for… Read more “Securing community land and resource rights in Africa: A guide to legal reform and best practices” ▸

Biocultural Community Protocols: A Toolkit for Community Facilitators

Integrated Participatory and Legal Empowerment Tools to Support Communities to Secure their Rights, Responsibilities, Territories, and Areas Click here to download the BCP Toolkit Edited… Read more “Biocultural Community Protocols: A Toolkit for Community Facilitators” ▸

Legal Review No 1 International Law and Jurisprudence

Legal Review No 1 International Law and Jurisprudence This report is part of a larger study conducted by the ICCA Consortium between 2011-2012, which… Read more “Legal Review No 1 International Law and Jurisprudence” ▸

Rights to Resources in Crisis: Reviewing the Fate of Customary Tenure in Africa

Rights to Resources in Crisis: Reviewing the Fate of Customary Tenure in Africa, Liz Alden Wily (2011) Briefs on Reviewing the Fate of Customary… Read more “Rights to Resources in Crisis: Reviewing the Fate of Customary Tenure in Africa” ▸

Mera Declaration of the Global Gathering of Women Pastoralists

Declaration: “Mera Declaration of the Global Gathering of Women Pastoralists” (2010) Summary: A global gathering of women pastoralists in Mera, India, from 21-26 November… Read more “Mera Declaration of the Global Gathering of Women Pastoralists” ▸

Land Rights Reform and Governance in Africa How to make it work in the 21st Century?

Land Rights Reform and Governance in Africa – How to make it work in the 21st Century?, Liz Alden Wily (2006) Discussion paper. ©… Read more “Land Rights Reform and Governance in Africa How to make it work in the 21st Century?” ▸

Traditional agricultural landscapes and community conserved areas: an overview

Peer-reviewed article: ”Traditional agricultural landscapes and community conserved areas: an overview” Jessica Brown and Ashish Kothari (2011) Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal,… Read more “Traditional agricultural landscapes and community conserved areas: an overview” ▸

Global reports: Indigenous peoples and communities are among the most at risk for defending their lands and territories and the environment

Sobering reports by Front Line Defenders and the UN Special Rapporteur on human rights defenders find that people defending land, environmental and Indigenous peoples’ rights were the most targeted and at risk for both lethal and non-lethal attacks. Read more ▸

CICADA Launches Four Policy Briefs on Biocultural Diversity

CICADA, ICCA Consortium Member, launched the first four policy briefs of its series on biocultural diversity in settler state contexts. They identify challenges, explore opportunities, and provide recommendations on: biocultural indicators and the nexus of nature, culture, and well-being; livelihoods, food sovereignty, health, and well-being; information and communications technologies; and territorial defense in extractive contexts. Read more ▸

Natural Justice Launches the Third Edition of the Living Convention

On International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples, Natural Justice (ICCA Consortium Member) launched the third edition of the Living Convention. The Living Convention is a response to this important and often-asked question: “What are the rights of Indigenous peoples, local communities, peasants and their organisations at the international level?” It provides a foundation to ensure people are in a stronger position to understand the law, shape the law and use the law. Read more ▸

ICCA Consortium Joins Global Solidarity Letter Against Aggressive Opportunism of Mining Industry During COVID-19

We have joined more than 330 other organisations condemning the continued operation of the mining industry amidst a global pandemic, environmental rollbacks and crackdown on civil society action. Read more ▸

Respuestas Comunitarias de los Territorios de Vida en Ecuador a la Emergencia

En Ecuador, los Pueblos Indígenas y comunidades locales han desplegado diferentes respuestas frente a la situación actual de emergencia, basadas en sus costumbres y en su cosmovisión. En este artículo, nuestro Miembro ALDEA analiza y documenta esta variedad de respuestas comunitarias. Read more ▸

The Evolving Crisis in Sinjajevina

Last September, we published an alert about Sinjajevina, Montenegro, where local communities and civil society were organizing to defend their pasturelands, in the face of government plans to occupy and use it as a military artillery testing range. Our Honorary member Pablo Domínguez tells us how the Sinjajevina communities have been confronting the crisis since then. Read more ▸

Defining Consent: Indigenous Peoples Reclaiming Decision-Making Authority and Governing Territories Through FPIC Protocols

ICCA Consortium Member Forest Peoples Programme released a new publication with three different case studies that show how Indigenous peoples have developed protocols for decision-making and territorial governance in Latin America (the Wampis, ICCA Consortium Member, the Juruna and the Embera Chami). Read more ▸

Nicaragua’s Failed Revolution: The Indigenous Struggle for Saneamiento

This new report, authored by our Honorary member Anuradha Mittal for the Oakland Institute, details the incessant violence facing the Indigenous communities in the Caribbean Coast Autonomous Regions of Nicaragua and provides in-depth information about the actors involved. It breaks the silence and calls attention to the Indigenous peoples’ ongoing struggle for their territories. Read more ▸

Big Football Team Mega-Mall vs. Galician Local Community Forest

As the community forest of Monte Veciñal en Man Común de Tameiga (Spain) is threatened by the construction of a mega-mall owned by a football team, the local community is defending its commons, with the support of Iniciativa Comunales (ICCA Consortium Member). Read more ▸

Global Report Identifies Land, Environmental and Indigenous Peoples’ Rights as Most Dangerous Sector for Human Rights Defenders

With growing global concern over our climate and ecological crises, those who defend Mother Earth should be gaining better protection – but instead, they are being targeted. According to Front Line Defenders’ annual global analysis, the fight for land, environmental and indigenous peoples’ rights was the most dangerous sector for defenders, comprising 40% of the human rights defenders killed in 2019. Read more ▸

“Criminalised for Defending Our Planet” – ICCA Consortium Supports Policy Brief as Part of Global Mobilisation Against Criminalisation

This 8-page policy brief explains different ‘stages’ of criminalisation and their effects on individuals and communities, especially women, and sets out key recommendations for ending the criminalisation of those who defend Mother Earth. Read more ▸

Video: Interview with Julio Cusurichi about the Defense of the Territory in the Amazon

Ashish Kothari interviews Julio Cusurichi, indigenous leader of the Shipibo people and President of ICCA Consortium Member FENAMAD, about territorial defense, threats, hopes and proposals of the communities represented by FENAMAD. Read more ▸

Water Flowing Up the Mountain: Development Devours Forest Reserve

A forest reserve outside Zambia’s capital has been shrunk significantly to make way for housing and lifestyle developments. Even worse, these new developments are pumping sewage into the Chalimbana River and contaminating the fish and water that local communities rely on. Local activists, like Robert Chimambo (ICCA Consortium Honorary member), are struggling to protect the river and forest, and hope to turn this territory into a community protected forest area. Read more ▸

Manual de Protección a Defensores Indígenas de los Derechos Colectivos sobre sus Tierras, Territorios y Medio Ambiente

La Federación por la Autodeterminación de los Pueblos Indígenas (FAPI), Miembro del Consorcio TICCA, publicó este manual de protección dirigido a los pueblos indígenas que defienden sus tierras, territorios y el medio ambiente. En el contexto de la movilización global contra la criminalización de las y los defensores, nos parece importante compartir este valioso recurso. Read more ▸

New Report: The Challenge of Protecting Community Land Rights

Between 2009 and 2015, Namati (ICCA Consortium Member) and its partners supported more than 100 communities to document and protect their customary land rights. In late 2017, Namati evaluated the impacts of its work on the communities’ responses to outsiders seeking community lands and resources. Realized by Rachael Knight, Honorary member of the ICCA Consortium, this report describes the outcomes of this evaluation and aims to shed light on how to strengthen global efforts to protect community land rights. Read more ▸

The 9th Southeast Asian Conference on Human Rights and Business

During the conference held in the Philippines, delegates released the Bata’an Statement, committing themselves to continued collaboration on tackling business related human rights abuses in the region, as well as calling on businesses and states to address these abuses. Helen Tugendhat and Hannah Storey from Forest Peoples Programme (ICCA Consortium Member) share the outcomes of the event. Read more ▸

From Transition to Domains of Transformation: Getting to Sustainable and Just Food Systems through Agroecology

In this new paper on agroecological transformations for just and sustainable food systems, Michel Pimbert (ICCA Consortium Honorary member) and his colleagues analyze the enabling and disabling conditions that shape agroecology transformations, and the ability of communities to self-organize within territories. Read more ▸

Yes To Life, No To Mining Launches new ‘Emblematic Cases’ From Frontline Communities

A new collection of interactive case studies from the Yes to Life, No to Mining Network, of which the ICCA Consortium is part, shares the stories of communities resisting mining, restoring damaged ecosystems, and protecting and developing alternatives to extractivism. Read more ▸

COICA declares the Amazon in Environmental and Humanitarian Emergency and Calls to Solidarity

As the Amazon forest continues to burn for more than 20 days without effective action being taken by the Brazilian and Bolivian governments, COICA is calling out to international allies for solidarity and urgent assistance, to gather funds to stop fires and help local communities recover. Read more ▸

Welcome to Thaidene Nëné, the Northwest Territories’ Newest National Park

It’s historic! “Achieving the protection of Thaidene Nëné for the Łutsël K’e Denesǫłine is a decades-long dream, and a critical step towards ensuring that our way of life can be maintained and shared with all Canadians,” said Chief Marlowe. Read more ▸

First published on 05/29/2016, and last updated on 04/30/2020